Hello, friends! Finnley the Dolphin here, swimming back onto your airwaves for another Audio Adventure. When you think of dolphins on television, there is one name that leaps right out of the water: Flipper. That smiling superstar of the 1960s seemed to solve every problem with a splash, a whistle, and a well-timed tail flip. For many children, Flipper was their first introduction to the idea of dolphins as companions, protectors, and even heroes of the sea.

But here is where we need to take a pause, just for a moment. The dolphins who brought Flipper to life were not roaming free with their pods in the open ocean. They were kept in tanks and trained to perform on cue. Behind the curtain of television magic, they endured confinement and stress that no sparkling lagoon could disguise. The show was a fantasy, and while it charmed millions, the reality was far less kind to the animals themselves.

Still, the history of Flipper is worth exploring. It connects film, television, records, and even the changing conversation about how humans treat marine life. It is a story filled with catchy theme songs and childhood nostalgia, but also one that reminds us how easily entertainment can gloss over suffering. So grab your snorkel, adjust your fins, and let us dive into the hidden story of Flipper, looking at both the glitter and the shadows beneath the waves.

In the mid-1960s American television was filled with programs designed for family viewing, and Flipper was one of the most recognizable. The series ran from 1964 to 1967 on NBC, filmed mostly at the Miami Seaquarium and Ivan Tors Studios in North Miami. It followed park ranger Porter Ricks and his two sons, Sandy and Bud, who lived along the Florida coast with their dolphin companion. The setup mirrored the formula of earlier animal shows where the pet is the hero that saves the day. The program’s cheerful tone covered up the realities of working with live dolphins in a confined setting.

Across its 88 episodes, Flipper presented stories where the dolphin acted as rescuer, problem solver, and occasional comic relief. The writers leaned on predictable formulas but kept audiences tuned in by pairing undersea photography with family drama. Some episodes highlighted environmental concerns, although these were usually simplified for younger viewers. The use of multiple dolphins to portray one character gave the illusion of a single, intelligent animal guiding the plot. Children across the country accepted the character as real, while the details of production stayed behind the curtain.

The series was a direct continuation of two feature films: Flipper (1963) and Flipper’s New Adventure (1964). The first film starred Chuck Connors as fisherman Porter Ricks, Kathleen Maguire as his wife Martha, and Luke Halpin as their son Sandy. The sequel followed Halpin again and introduced a new set of adventures that made the character popular enough to move to television. When the show launched in 1964, the cast shifted: Brian Kelly stepped in as the widowed park ranger Porter Ricks, Luke Halpin continued as Sandy, and Tommy Norden joined as Bud, the younger brother. This blend of continuity and fresh casting tied the television series back to the films while giving it a new family structure.

By the time reruns circulated in the late 1970s and 1980s, Flipper had become shorthand for wholesome sea life adventure. The show’s light stories masked the practical challenges of training and caring for dolphins in captivity. Later anniversaries at the Seaquarium brought back actors Luke Halpin and Tommy Norden to meet new generations of fans. For many viewers the series remains a nostalgic artifact of childhood afternoons. Beneath that memory is the complex reality of how the animals and people behind it lived.

The dolphin who started it all was Mitzi, sometimes spelled Mitzy. She played the original Flipper in the 1963 feature film, swimming alongside Luke Halpin and Chuck Connors. The movie’s success made her the first animal associated with the role, and her performance became the blueprint for the character’s personality on screen. She was trained to interact with actors, follow boats, and perform on cue in ways that delighted audiences and made the story believable. For many viewers of the time, Mitzi was Flipper, and her image carried into promotional campaigns and movie posters.

Mitzi lived at the Miami Seaquarium, where she remained even after her role in the film. Though she did not appear in the television series as often as the other dolphins, her part in launching the franchise made her the most historically recognized of them all. She died in 1972 at the age of 14, which was considered young for a bottlenose dolphin. After her death, she was buried on the Seaquarium grounds, where a bronze plaque still marks the site with the inscription “Mitzi – The Original Flipper.” Visitors continue to stop at the memorial, connecting the show’s nostalgic memory with the real animal who began the story.

Another dolphin remembered by name is Kathy, who was used frequently in the television series during the mid-1960s. She was the one most often in close interaction with Luke Halpin and Tommy Norden, which made her stand out among the group of dolphins that rotated through the role. In 1968, trainer Ric O’Barry recalled that she surfaced slowly, took a breath, looked at him, and then sank without exhaling. He believed that she had chosen to stop breathing, calling it suicide. His account would later become one of the most cited stories in debates about dolphin captivity.

The impact on O’Barry was immediate and life-changing. Up to that point, he had built his career teaching dolphins to perform tricks for the screen and for marine parks. Kathy’s death convinced him that these animals could not thrive under such conditions. From then on, he turned away from show business and founded the Dolphin Project, a group dedicated to ending dolphin captures and promoting sanctuaries. For him, Kathy’s death marked the dividing line between a career in entertainment and a life in activism. Her story remains powerful because it links the cheerful world of children’s television with the stark realities of keeping dolphins in tanks.

The last of the original Flipper dolphins to survive was Bebe. Born at the Miami Seaquarium in 1956, she was already a resident when filming began and became part of the group used for the television series. Unlike Kathy, Bebe lived for decades, long after the show had ended and audiences had moved on. She gave birth to multiple calves during her years in captivity, and some of her offspring were also used in shows at the park. Her role in the series was less publicized at the time, but her longevity eventually made her significant.

Bebe died in 1997 at the age of 40, which was unusually old for a dolphin in captivity. Her death was covered by newspapers, noting that she had been the last surviving dolphin from the original NBC program. Trainers and staff remembered her as hardy and outgoing, qualities that allowed her to live far beyond what many expected. With her passing, a living connection to the 1960s production was gone, leaving only memory, recordings, and the plaque for Mitzi. Together, Bebe’s endurance and Kathy’s tragedy frame two very different outcomes of the same story.

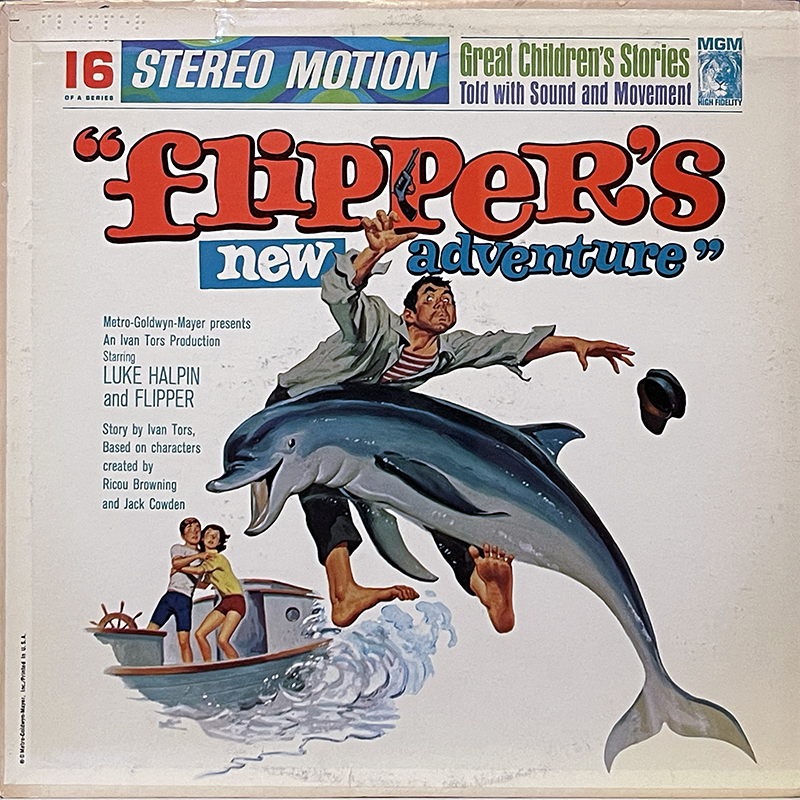

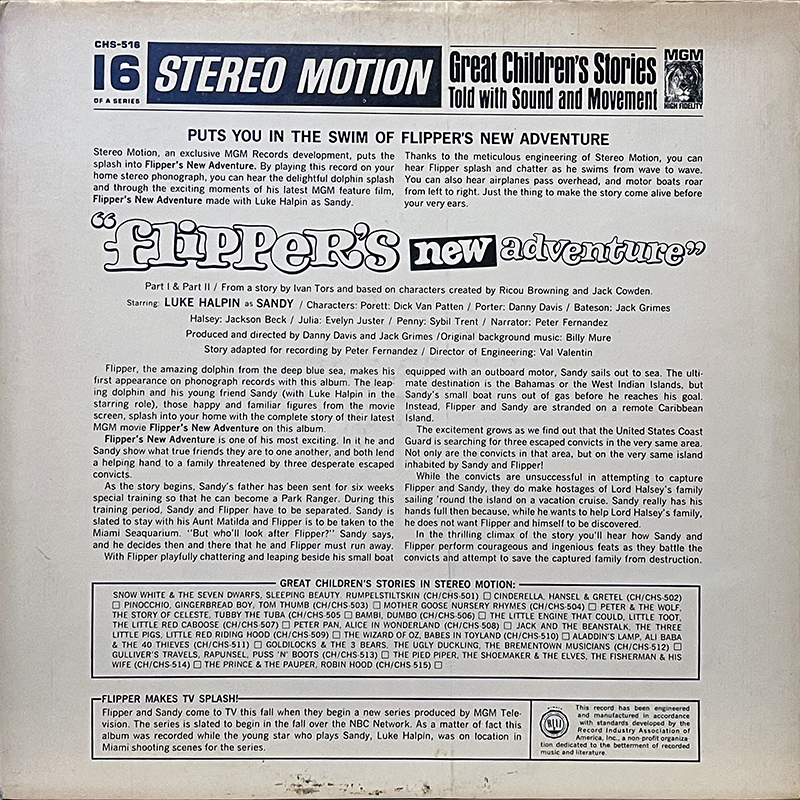

The program’s reach was not limited to film and television. Record labels also saw an opportunity to extend Flipper into children’s bedrooms and living rooms through vinyl. MGM Records, established in 1946 by Loew’s Incorporated, had built its name on movie soundtracks before branching into pop, jazz, and children’s material. By the late 1950s the company had developed a line called Great Children’s Stories in Stereo Motion, marketed as immersive listening experiences that promised moving sound effects through stereo channels. It was in this series that Flipper appeared as catalog number CHS-516.

The record, titled Flipper’s New Adventure, was released in 1964 to coincide with the second film. The story was dramatized across two sides, featuring Luke Halpin reprising his role as Sandy and supported by voice actors Dick Van Patten, Jackson Beck, Evelyn Juster, Sybil Trent, and Jack Grimes. Narration was provided by Peter Fernandez, later known as the voice of Speed Racer. Production credits went to Danny Davis and Jack Grimes, while the guitar-driven background music came from Billy Mure. For children listening at home, this was a way to relive the movie without leaving the record player.

The album cover presented an image of Flipper hurling a villain from the sea while Sandy and a companion looked on in admiration. Promotional copy on the back suggested listeners could hear splashes, airplane flyovers, and motorboats crossing the stereo field. Such claims spoke to the fascination of the time with stereo sound, where the effect was sometimes more important than the story itself. Positioned among fairy tale titles in the same series, the Flipper record confirmed the dolphin’s place as a storybook character as much as a screen figure.

Sound was central to this construction, and here lies another hidden layer. The distinctive voice of Flipper was not taken from dolphins at all but from the manipulated call of a kookaburra bird, chosen for its sharp and lively tone. This invented sound became the trademark “speech” of the character, recognizable to audiences everywhere. It was an artistic decision rather than a scientific one, reflecting how television built its own version of nature for mass appeal.

Dolphins do communicate with whistles and clicks, but their hearing extends far beyond the range of most human ears. Their sensitivity surpasses the frequency of a ship’s klaxon, which on the show was often portrayed as a way to summon Flipper. In practice such a signal would have made little sense. The effect was staged for audience belief, not biological accuracy. Much like the kookaburra voice, the horn was a reminder that the series belonged more to the world of entertainment than to the sea it claimed to represent.

The stories of Mitzi, Kathy, and Bebe reveal a truth that the bright colors of television and record sleeves never showed. These dolphins were moved in crates, confined to tanks, and forced to repeat behaviors for the sake of filming schedules and paying crowds. Trainers withheld food to reinforce tricks, and the animals endured stress from noise, transport, and constant human handling. What looked like playful leaps on screen were often the result of conditioning and exhaustion. Their lives were managed entirely by the demands of production, rather than the rhythms of the ocean.

The suffering was not unique to Flipper. The same practices continued in marine parks around the world, where dolphins and whales were turned into exhibits. Deprived of their social groups and open waters, many displayed signs of distress: pacing in circles, floating motionless, or injuring themselves on tank walls. The smiling appearance of a dolphin hides the fact that the expression is permanent, not an indicator of joy. These animals, intelligent and social by nature, were reduced to props in a spectacle built for human entertainment.

And so, friends, we come to the end of this adventure through reels of film, grooves of vinyl, and the long shadows cast behind the spotlight. Flipper was a star on the screen and a household name on record sleeves. The dolphins who carried that role lived lives that television magic could never change. Their leaps and whistles delighted millions, yet they were confined, transported, and trained in ways that stripped away the freedom of the open sea.

I share this to remind us that behind the cheerful image there were living beings who deserved more than a tank and a schedule of performances. Mitzi, Kathy, Bebe, and the others were dolphins with their own stories, and their lives were altered for our entertainment. To honor them, we need to look past the glossy fiction and face the truth of what captivity means.

Every ticket to a marine park is a sentence to captivity, a life behind glass, cut off from the wild we were born to roam.

Speak out.

Take a stand.

Do not buy the ticket.

Demand freedom.

Empty the tanks.

Sources:

Barrantes, Nicole. “The Hidden Cruelty Behind the Show Flipper.” World Animal Protection, 24 May 2023, https://www.worldanimalprotection.us/latest/blogs/hidden-cruelty-behind-show-flipper. Accessed 26 Aug. 2025.

“Billy Mure.” Discogs, https://www.discogs.com/artist/45872-Billy-Mure. Accessed 26 Aug. 2025.

“Danny Davis (4).” Discogs, https://www.discogs.com/artist/1232670-Danny-Davis-4. Accessed 26 Aug. 2025.

“Flipper (1963).” IMDb, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0057063/?ref_=fn_all_ttl_2. Accessed 26 Aug. 2025.

“Flipper.” Nostalgia Central, https://nostalgiacentral.com/television/tv-by-decade/tv-shows-1960s/flipper. Accessed 26 Aug. 2025.

Holloway, Henry. “Heartbreaking Story of Dolphin Named Kathy Who Played TV’s Flipper before ‘Drowning Herself’ in Beloved Trainer’s Arms.” The U.S. Sun, 22 Sept. 2021, https://www.the-sun.com/news/3701375/dolphin-kathy-flipper-killed-herself. Accessed 26 Aug. 2025.

“Luke Halpin Biography.” IMDb, https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0356983/bio/?ref_=nm_ov_bio_sm. Accessed 26 Aug. 2025.

Miami Herald Archives. “Before the Football Team, a Miami Dolphin Got Its Own TV Show. The Star Was Flipper.” Miami Herald, 14 Sept. 2019, https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/community/miami-dade/article235003132.html. Accessed 26 Aug. 2025.

“MGM Records.” Discogs, https://www.discogs.com/label/33261-MGM-Records. Accessed 26 Aug. 2025.

“Various – Flipper’s New Adventure.” Discogs, https://www.discogs.com/release/10749916-Various-Flippers-New-Adventure. Accessed 26 Aug. 2025.