Hi there! I’m Finnley, your aquatic guide through the weirder side of recorded sound. Today’s audio adventure features a center-start Pathé disc, which means the needle starts in the middle and works its way out. That alone tells you this isn’t going to be a typical listening session. These records use vertical grooves and were meant to be played at 90 revolutions per minute, using equipment that isn’t exactly easy to find anymore.

This post takes a look at what these records were, how one was recorded using modern gear, and what it took to make it sound close to how it was originally intended. I’ll walk you through the background of the Pathé format, the specific record used, and the cleanup process. There were a few extra steps involved due to the groove type and playback speed. But with a little patience and some careful adjustment, the recording was made audible again. Let’s take a closer look.

In the first years of the 20th century, recorded sound existed in several competing forms. One of those formats was developed by Pathé Frères, a company based in France. Their engineers chose a design that featured vertically cut grooves and required the stylus to begin at the center of the disc. This system was introduced to the public around 1905 and was not compatible with the lateral-cut formats that became more common in later years. Pathé sold the discs along with their own branded phonographs, which were built to accommodate the vertical tracking and center-start design.

The discs were large and often played at 90 revolutions per minute. The grooves were shallow and required a specific type of stylus, made of sapphire and rounded to suit the vertical motion of the recording. Instead of printing paper labels on the surface, the company etched information directly into the shellac. This included the catalog number, title, and sometimes the performer or instrumentation. The disc would begin playing from the inner groove and end near the outer edge, which was opposite of how most other records were played at the time.

Over time, Pathé established manufacturing and distribution operations outside of France. In the United States, they operated through a branch known as the Pathé Frères Phonograph Company. In Europe, their activities were managed by a company called Compagnie Générale des Machines Parlantes Pathé Frères, which had been created in 1919. By 1924, the Pathé family sold their international phonographic interests to the Marconi Company. This included their factories and catalog rights outside the United States. The Pathé brand was then transferred several more times through various acquisitions and mergers involving Columbia Graphophone and later Electric and Musical Industries Ltd.

In 1931, Columbia Graphophone merged with The Gramophone Company to form EMI. This new structure absorbed Pathé’s European operations, which continued under the name Pathé Marconi. Although the original vertical-cut format was no longer being produced, the label name remained active for decades. In the United States, the story was different. Pathé became part of the Cameo Recording Company in 1927 and was absorbed into the American Record Company two years later. The Pathé label name disappeared from the U.S. market by 1931.

Even though the center-start disc format had ended, the Pathé name continued to appear on later releases in other parts of the world. Pathé Marconi EMI issued records throughout the mid-to-late 20th century, although those records followed the standard lateral-cut format. The trademark was held by EMI Music France S.A.S. until March 2013. By that time, the label had long since stopped producing the original disc format, but its history remained part of the larger story of recorded sound. These transitions show how a format may become obsolete while the name associated with it continues under different ownership and structure.

The changes in ownership and format reflect larger shifts in how audio was recorded and distributed. However, the technical features of the disc itself are what define the Pathé format most clearly. In the next section, one specific example will be examined in detail, including the process used to play and restore it.

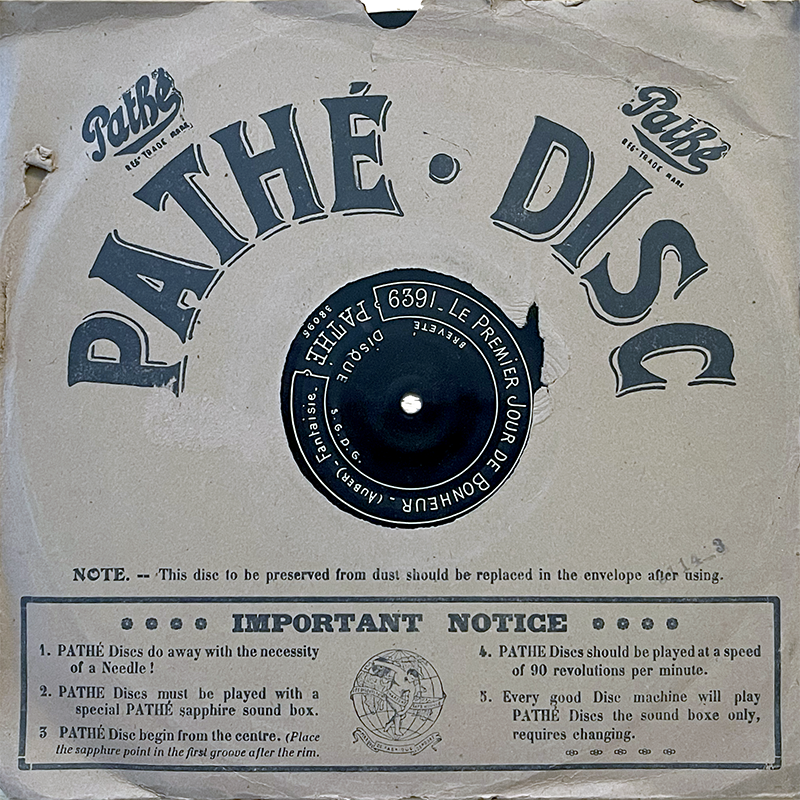

The record played in this project was issued during the vertical-cut era and features two selections, one on each side. Both sides use the center-start groove structure and show signs of the mechanical process used in Pathé’s shellac production. The labels are etched into the surface of the record rather than printed. The background is black, and the text is white, with catalog numbers and titles included in French. The sleeve that came with the record contains instructions in English, which suggests it may have been distributed through Pathé’s U.S. branch.

One side is labeled “L’Ombre – Fantaisie, Baryton (Flotow)” with catalog number 5018. The English translation of the title is “The Shadow – Fantasy, Baritone.” This track appears to be an operatic selection based on Friedrich von Flotow’s lesser-known work L’Ombre. The recording likely features a piano and a baritone vocalist, although no performer is named on the disc. This lack of individual credit was common in Pathé’s vertical-cut catalog during this period.

The other side is labeled “Le Premier Jour de Bonheur – Orchestre et Chœurs” with catalog number 6391. The English translation is “The First Day of Happiness – Orchestra and Choirs.” This selection is drawn from an operetta composed by Daniel Auber and features orchestral and choral parts. Like Side A, it was manufactured using the same vertical groove structure and etched label process. The disc contains no additional notes about the performers or recording date. Playback instructions printed on the sleeve specify the use of a special stylus and tonearm weight, as well as the required 90 RPM speed.

Playing and digitizing the disc involved a number of limitations. The record was played using a modern quartz-locked turntable set to 78 RPM. Although the speed was close to the intended 90 RPM, it was not exact. In addition, the stylus used was designed for shellac 78s, not vertical-cut grooves. This created some tracking distortion and frequency imbalance. After digitizing, the audio and video were adjusted by approximately 15 percent to bring the playback closer to the correct pitch and tempo. Further digital cleaning was applied to reduce surface noise and address the limitations caused by using a lateral stylus on a vertical-cut recording.

The handling and playback of this disc required a mixture of analog compromise and digital correction. The result offers a practical way to hear the original material, even if the process does not fully reproduce the intended playback experience. In the final section, the long-term significance of the Pathé disc format will be considered, including the ways it continues to affect preservation and audio history.

The Pathé disc format has specific mechanical and historical characteristics that set it apart from other early record formats. It used a groove cut that moved vertically, a playback direction that started at the center, and required equipment designed to match those specifications. These conditions made it difficult to adopt Pathé records across competing platforms. The company responded by selling integrated systems, where discs, players, and accessories were developed to work together. Over time, this model became harder to maintain as the rest of the industry adopted lateral-cut records with outside-start grooves.

Today, vertical-cut Pathé discs are considered difficult to play correctly without modified equipment. Their groove geometry does not match the shape or movement of modern stylus assemblies. Some collectors have adapted turntables for vertical playback, while others rely on digital processing after making a standard transfer. Archival institutions have documented restoration methods for Pathé discs that involve realigning cartridge angles or applying software correction to simulate vertical stylus motion. These methods allow the content to be preserved and made available, even when the original hardware is no longer functional.

The Pathé name continued to exist even after the disc format disappeared. Under Pathé Marconi EMI, the label released music in standard LP and single formats during the mid and late 20th century. These newer products did not use vertical grooves or center-start design, but they carried the same branding. The reuse of the name helped maintain continuity for marketing and cataloging purposes. Although these later records are unrelated in format, they reflect the long shadow cast by the original Pathé brand.

The label’s exit from the U.S. market around 1931 did not prevent it from surviving in other parts of the world. In France and some parts of Asia, the Pathé name continued to appear on releases for many decades. These later records were often indistinguishable from other EMI products except for the label imprint. The brand persisted until 2013, when EMI Music France no longer held the trademark. By then, the original vertical-cut format had long since become a subject of historical interest rather than consumer use.

What remains is a format that requires careful handling, specific playback knowledge, and ongoing attention from archivists. The Pathé disc may no longer be a part of everyday listening, but its structure and presentation reflect a time when recorded sound followed many different paths. Its presence in collections today is a result of both physical survival and the willingness of listeners and researchers to engage with a format that did not follow the dominant path. It serves as a reference point in the timeline of audio formats and continues to inform how preservation work is approached.

Bringing this record to you involved a bit of compromise. It was played using a 78 RPM stylus on a vertical-cut disc, so the equipment didn’t line up perfectly. After recording, the speed was adjusted to match the original 90 RPM, and some noise was filtered out to make the content easier to hear. What you’re listening to now isn’t a restored version. it’s a playback that shows what’s still there when the disc is handled carefully.

Formats like this don’t show up often, but they’re still worth exploring. They reveal how much experimentation went into recorded sound before things became more standardized. I’ll be continuing to dig up more of these unusual formats and finding ways to share them here. Thanks for swimming by. I’ll see you next time on another one of Finnley’s Audio Adventures.

Sources:

Copeland, George A., et al. Pathé Records and Phonographs in America, 1914–1922. Mulholland Press, 2000. pp. 8, 57, 60.

Copeland, Peter. Manual of Analogue Sound Restoration Techniques. British Library, 2008. p. 88.

Holmes, Thom. The Routledge Guide to Music Technology. Taylor & Francis, 2013. pp. 229–230.

“Pathé.” Discogs, https://www.discogs.com/label/70230-Pathé?role=Label&format=90+RPM&format=Pathé+Disc&searchParam=6391. Accessed 6 Aug. 2025.