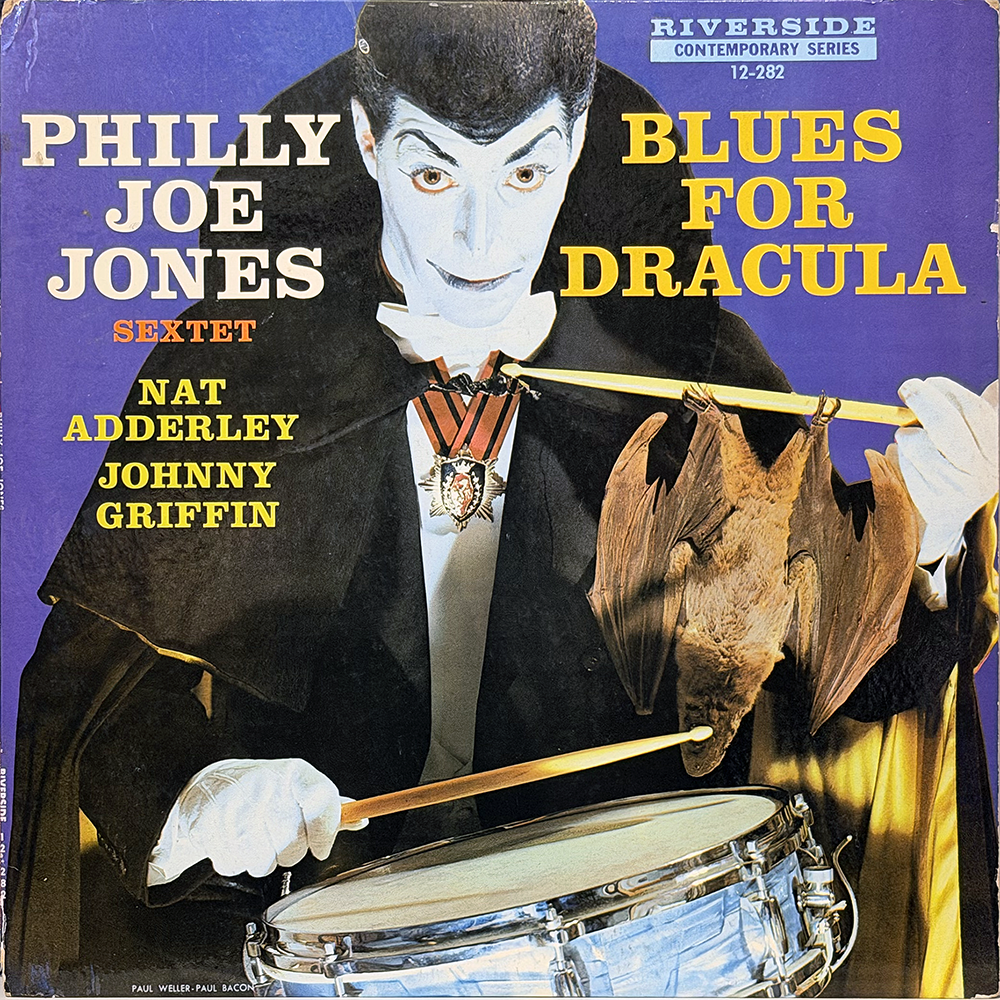

Hello swimmers, and welcome back to another depth sounder into the grooves of vintage jazz curiosities. Today’s selection surfaces not just from the back bins of Riverside Records, but from a place where swing walks hand in hand with theatricality. The album in question is Blues for Dracula, a 1958 release by the Philly Joe Jones Sextet. While its cover might suggest novelty, the record itself offers a layered portrait of post-bop discipline. Through a dive into the life of Philly Joe Jones, a look at the musicians who accompanied him, and a detailed inspection of the record’s contents and historical context, this post aims to decode why Blues for Dracula continues to echo beneath the stylus.

Born Joseph Rudolph Jones in Philadelphia on July 15, 1923, Philly Joe Jones became a defining voice in modern jazz drumming through a career that spanned four decades. Raised in a musical environment, Jones learned piano in his youth before turning his attention to the drums, where he found a powerful expressive outlet. His early work included stints with local R&B bands, but his skill and adaptability soon led him to more prominent engagements. By the 1950s, Jones had become a core member of the Miles Davis Quintet, contributing to a body of recordings that remain central to the development of hard bop. Known for his crisp articulation, layered rhythms, and subtle command of swing, Jones was respected not only as a sideman but also as a bandleader and educator. Despite facing challenges later in life, including periods of addiction and underemployment, he remained committed to music until his death from a heart attack on August 30, 1985, in his native Philadelphia.

Jones was a drummer who carried with him a deep belief in the structure and intention behind music. He resisted trends that he felt undermined the discipline of jazz, particularly the rise of so-called “freedom music” that lacked grounding in formal technique. In a 1969 interview, he stated, “Music isn’t noise.” His approach combined deep knowledge of tradition with a personal philosophy of clarity and directness. Even his theatrical gestures such as performing as Dracula on this record were executed with an ear toward precision rather than spectacle. His teaching work later in life, including at clinics and conservatories, carried this philosophy forward, encouraging younger players to understand the importance of roots and repetition before innovation.

Though sometimes overshadowed by other drummers of the era, Jones held a distinct role in the lineage of jazz percussion. Critics and fellow musicians acknowledged his ability to blend melodic sensitivity with rhythmic force. He was not simply a timekeeper, but rather an orchestrator behind the kit, capable of guiding a band’s emotional direction through tone and tempo. As his career progressed, he continued to record and perform, often in Europe, where he found both an appreciative audience and relative stability. Even late in his life, his performances carried a strong sense of purpose, recalling the energy of his youth with added depth from years of lived experience. His death, just days before Jo Jones (no relation), marked the end of an era in jazz drumming.

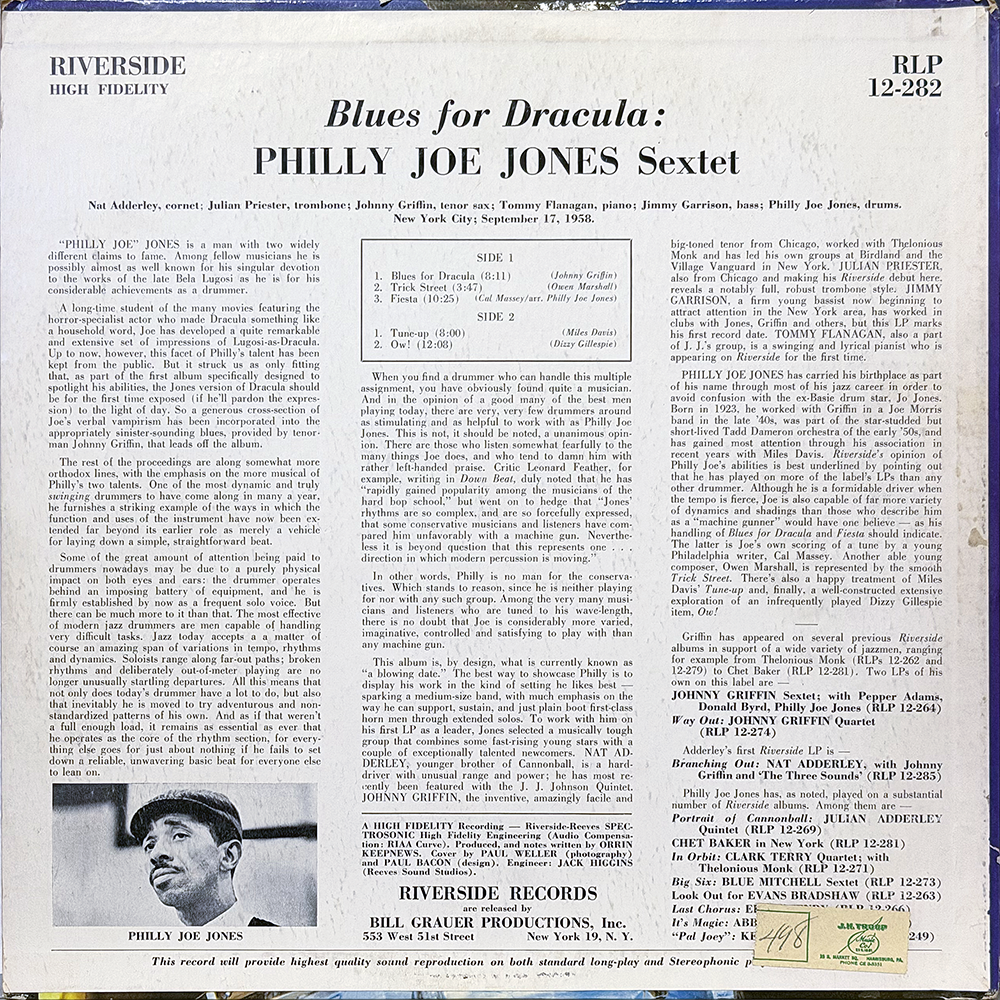

The personnel includes several musicians who would go on to shape jazz in various capacities. Cornetist Nat Adderley, trombonist Julian Priester, tenor saxophonist Johnny Griffin, pianist Tommy Flanagan, and bassist Jimmy Garrison round out the sextet. Each brought their own sensibilities and trajectories to the session, resulting in a recording that functions as both a showcase for Jones and a meeting ground for rising and established talents. Their careers would intersect with numerous jazz legends, and many of them would become leaders in their own right. Understanding their backgrounds adds dimension to the record and helps contextualize the music as more than a novelty.

Nat Adderley, born in Tampa, Florida, was the younger brother of Cannonball Adderley and a respected player in his own right. He played cornet with a brassy clarity and was known for his role in the soul-jazz movement that followed hard bop. By the time he joined Jones on this session, Adderley had already played with a variety of ensembles and would go on to work with his brother’s quintet throughout the 1960s. He also contributed as a composer and talent scout. His legacy includes not only numerous recordings but also a family lineage of musicians, as his son, Nat Adderley Jr., became a successful keyboardist and producer. His appearance on Blues for Dracula situates him at a productive intersection of emerging trends in late-50s jazz.

Tommy Flanagan, the pianist on this record, brought a lyrical and harmonically rich approach to the keyboard. Born in Detroit in 1930, Flanagan had already participated in sessions for landmark albums such as Saxophone Colossus and Giant Steps by the time he joined Jones’ sextet. Known for his understated style, he played with singers and horn players alike, offering support without overshadowing. He was a long-time accompanist to Ella Fitzgerald and appeared on dozens of records over the course of his career. His inclusion here demonstrates Jones’ preference for musicians who understood nuance and cohesion. Even when given room to solo, Flanagan rarely strayed from the melodic heart of a tune.

Tenor saxophonist Johnny Griffin brought a contrasting energy to the ensemble. Nicknamed “the Little Giant,” Griffin was known for his powerful tone and speed, as well as his deep familiarity with bebop vocabulary. Originally from Chicago, he had played with Art Blakey and Thelonious Monk, among others. His inclusion on Blues for Dracula reflects both his technical prowess and his ability to handle more playful material with sincerity. In one later interview he said he loved the “first record I put on voluntarily,” referring to Philly Joe’s work. Griffin moved to Europe in the 1960s, where he remained active in the jazz scene until his death in 2008. At the time of this recording, however, he was still closely tied to the American hard bop tradition. His performance on the title track stands as one of the more expressive moments on the album.

Julian Priester, the youngest member of the group, was a trombonist from Chicago who had worked with Sun Ra and Max Roach before joining Jones for this session. His playing blended the avant-garde with more structured swing, and his tone was well-suited for ensemble work. Priester would later play with Herbie Hancock and become involved in jazz education, but at this point in his career, he was still defining his place in the scene. His role on Blues for Dracula was both supportive and expressive, adding richness to the horn arrangements. He went on to lead his own projects and remains an important figure in both performance and pedagogy. As he once recalled in an interview, “I learned more from watching Philly Joe in one rehearsal than in a semester of theory classes.”

Jimmy Garrison rounded out the group on bass. Though born in Miami, he was raised in Philadelphia and shared regional ties with Jones. He is best known for his later work with John Coltrane, where he served as a steady, grounding force in some of the most exploratory music of the 1960s. Garrison brought a calm presence to this earlier session, offering solid support while also engaging melodically with the soloists. After Coltrane’s death, he worked with Alice Coltrane and Elvin Jones, and he also taught at institutions such as Bennington College. His early appearance on this record reveals the roots of his later voice, precise, measured, and rhythmically aware. The interplay between Garrison and Jones forms much of the album’s structural core.

Released on Riverside Records in 1958, the album is part of the label’s Contemporary Series and reflects both the independence and eclecticism that characterized Riverside during this period. Founded in 1953 by Bill Grauer and Orrin Keepnews, the label initially focused on reissues of traditional jazz before expanding into new recordings by modern artists. By the time of this album’s release, Riverside had become a haven for musicians seeking artistic flexibility and high production values. Sessions were typically recorded at Reeves Sound Studios in New York, with engineers and producers who understood the genre. Blues for Dracula fits into this framework while also standing slightly apart due to its theatrical concept.

The album opens with the title track, a medium-tempo blues featuring a spoken word intro by Jones in the role of Count Dracula. His voice, affected but rhythmically precise, sets the tone for what follows, a tightly arranged, well-executed tune that balances novelty and form. Other tracks include “Trick Street,” “Fiesta,” “Tune-Up,” and “Ow!,” each offering a different look at the ensemble’s capabilities. “Fiesta” features Jones’ own arrangement and provides an opportunity for longer-form exploration. “Ow!,” a Dizzy Gillespie composition, closes the record with an extended workout for all players. The album’s total length and variety make it more than a single-theme session; instead, it acts as a snapshot of six musicians in open yet disciplined conversation.

Produced by Orrin Keepnews, with design by Paul Bacon and photography by Paul Weller, the album’s presentation matches its sonic ambitions. The front cover features Jones in a Dracula cape, raising drumsticks like fangs. The image is humorous without being dismissive, and the visual pun aligns with the controlled theatricality of the music. The back cover offers liner notes that contextualize the record within Jones’ career and the broader Riverside catalog. The label’s practice of detailed credits and production notes enhances the historical value of the release. One critic noted that Jones “employs every supporting mechanism in the book,” including ensemble cues that recall Cozy Cole and Big Sid Catlett.

In reflecting on this album, one finds a project that functions on multiple levels: as entertainment, as artistic statement, and as a document of its time. The players involved would go on to diverse careers, but their shared moment in this recording offers a glimpse into the possibilities of collaborative jazz in the late 1950s. Jones used the Dracula persona not to distract but to invite, framing the session as something more than a studio exercise. His understanding of rhythm as structure combined with a willingness to play anchors the record in both tradition and invention. As drummer Arthur Taylor observed, “Philly Joe was the kind of cat who could show you the entire history of the drums in one solo.” For those willing to look past the cape, Blues for Dracula offers something worth revisiting. Its bite is gentle, but it lingers.

Thanks for swimming along with me on this eerie excursion into Riverside’s haunted wax. Blues for Dracula may wear a costume, but the grooves beneath are all substance. Whether you’re in it for the snappy brushwork, the sharp horns, or the vampire voice that kicks it all off, there’s something bubbling under the surface for every curious ear. Keep your shell to the stylus and your sonar tuned to the depths. We’ll resurface soon with another oddity from the deep archive. Until then, keep your records dry, your turntables level, and your cape pressed. This is Finnley the Dolphin, signing off from the groove lagoon.