Audio Only:

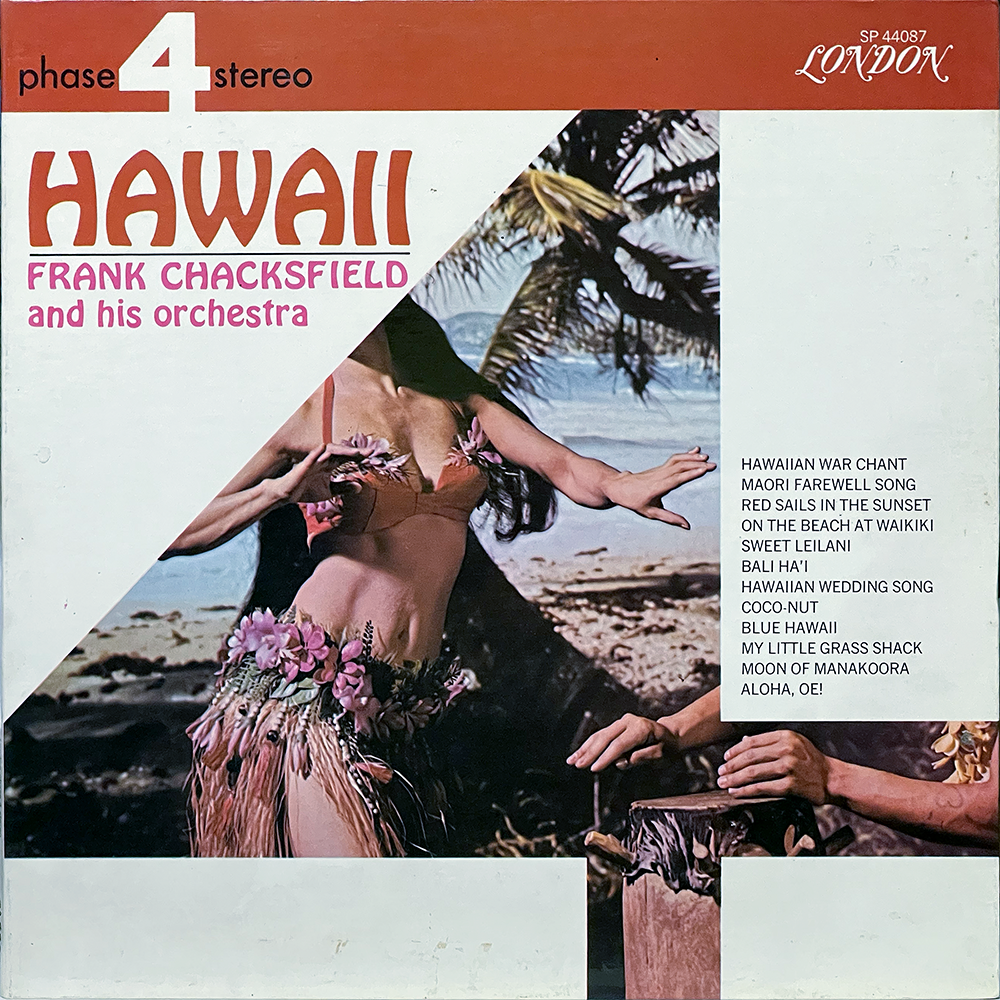

Aloha, fellow wave riders. Finnley the Dolphin here, paddling around near the bottom of the record bin for another gentle spin through sound. Today’s stop is somewhere warm and familiar, a postcard version of paradise shaped by orchestras and vinyl. We’re heading to Hawaii, the early-1960s LP by Frank Chacksfield, released in full Phase 4 stereo by London Records. This is not the clattering tiki-bar soundtrack some folks might expect. Chacksfield takes a quieter path, and it’s one worth spending some time with. So settle in, maybe imagine a breeze off the water, and let’s see what this record is really doing beneath its glossy surface.

When Hawaii became the 50th state in 1959, it touched off a wave of fascination across the mainland. Jet travel was becoming more accessible, and the idea of flying to the islands suddenly felt within reach. Families came home with souvenirs, home movies, and new ideas about leisure. Living rooms filled with rattan furniture and tropical patterns. Music slipped easily into that picture, offering an affordable way to bring the idea of Hawaii home.

Record labels were quick to respond. Hawaiian-themed albums flooded the market, each offering its own version of paradise. Some leaned heavily on exaggerated percussion or artificial stereo tricks. Others favored sweeping orchestral arrangements meant to suggest warmth and ease. What these records rarely offered was traditional Hawaiian music such as chants, hulas, or indigenous performance styles. Instead, they presented an Americanized and carefully sanitized sound, shaped to fit mainland expectations. These albums were often less about Hawaii itself and more about what Hawaii represented to listeners far away.

What people responded to was the mood. These albums offered calm, space, and a sense of pause. Accuracy was rarely the point. In that environment, Frank Chacksfield stood out by doing less, not more. His arrangements asked listeners to slow down and stay with the music rather than be dazzled by it.

Chacksfield never relied on novelty. His strength came from discipline and experience. Before he was known as a conductor and arranger, he played organ in church and performed at festivals. During the war years, he worked on arrangements for military broadcasts and postwar entertainment. By the time he reached the studio albums that made his name, he had complete control over large ensembles and a clear sense of restraint.

By the early 1960s, that approach had become his signature. Chacksfield’s records did not chase trends or attempt reinvention. He worked with familiar material and shaped it carefully, focusing on balance and tone. His earlier album South Sea Island Magic explored tropical themes without leaning on the louder clichés of the genre. That record set the template for projects like Hawaii.

The Hawaii album follows the same philosophy. The song choices are obvious and intentional, but the performances remain measured. There are no sudden shifts in energy or attempts to modernize the material. The arrangements move steadily, letting melody and texture do the work. That consistency gives the album a unified feel from start to finish.

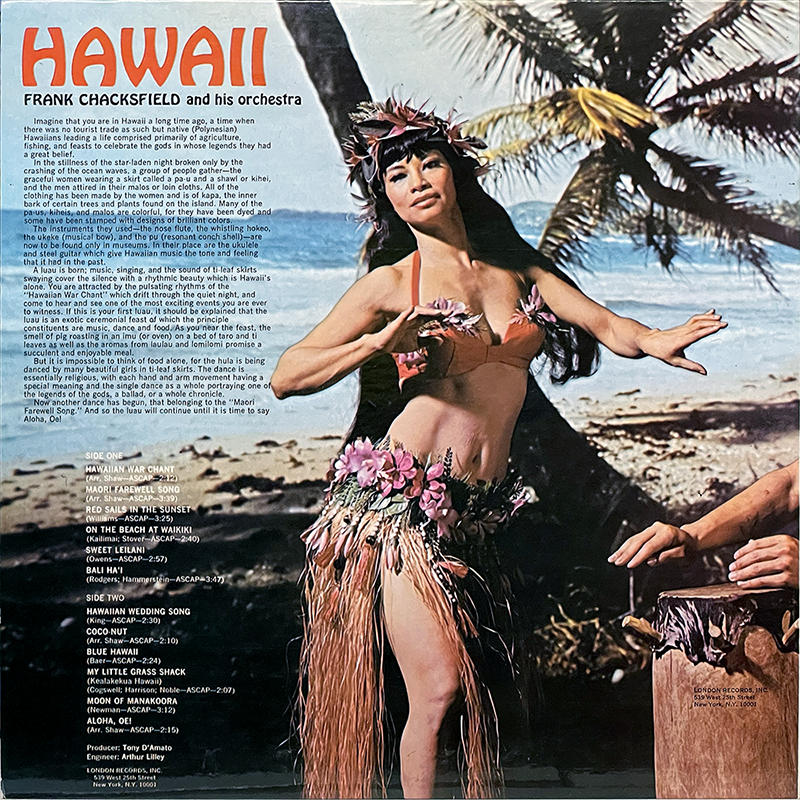

Much of that clarity is reinforced by how the record was made. Hawaii was recorded as part of London Records’ Phase 4 Stereo series, which launched in 1961 as an experiment in precision and control. Engineers worked with custom multi-channel mixers that allowed instruments to be placed deliberately within the stereo field. Instead of layering tracks after the fact, sessions were built live through the board.

Phase 4 recordings were carefully planned. Arrangements included instructions for placement, balance, and reverb. Stereo was treated as part of the composition rather than a final polish. The results were clean and vivid, but not cold. While some early Phase 4 releases leaned too heavily on spectacle, the sound matured quickly. By the time Hawaii was recorded, the process supported the music rather than overshadowing it.

“Hawaiian War Chant” opens the record with steady momentum. The rhythm builds without aggression, and the melody stays in focus. “Sweet Leilani” and “Blue Hawaii” slow things down, stretching into long, unhurried lines that encourage quiet listening. “My Little Grass Shack in Kealakekua” adds a touch of lightness without turning playful into cartoonish. The album closes with “Aloha, Oe!,” delivered with formality and restraint. It feels like a proper farewell, calm and unforced.

Produced by Tony D’Amato and engineered by Arthur Lilley, Hawaii holds its shape because it never reaches for excess. It is less a portrait of a place than a carefully constructed mood, shaped by distance and imagination. This is Hawaii as heard from a listening room, late in the evening, with the lights low and the turntable doing its quiet work.

Thanks for swimming along on another audio detour with me. If this one leaves you floating a little calmer than before, it’s worth tracking down and letting it play all the way through. Until next time, keep your flippers near the speakers and let the sound take you somewhere gentle. This has been another dive into the deep cuts with Finnley’s Audio Adventures.