Hi, I’m Finnley the Dolphin, and today’s dive takes us into the gentle surf of the 1960s budget record industry, where labels like Wyncote carved out a surprisingly influential niche. This isn’t just a story about a Hawaiian-themed album, it’s about a moment in time when stereo systems were the pride of the family room, and sound had become something to show off.

Let’s take a closer look at Hawaiian Paradise, from its wide stereo swells to its curious connections with magnetic film technology and mid-century American living rooms. There’s more beneath the surface than meets the ear.

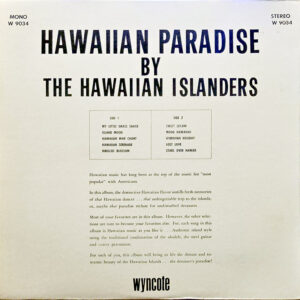

Dreams of luaus, cocktails, and tiki-lit nights come alive on Hawaiian Paradise, an album by The Hawaiian Islanders that captures an Americanized vision of Hawaii. Rather than presenting traditional Hawaiian music, it leans into the world of exotica, crafting lush soundscapes that reflect a mid-century fantasy of island life. Issued by Wyncote Records, a label more recognized for its affordability than its artistic prestige, the album nevertheless achieves a captivating ambiance through its use of steel guitar, relaxed tempos, and melodic phrasing evocative of ocean breezes and sandy shores. It represents a broader trend of exotica albums that promised escapism during a time when long-distance travel remained out of reach for many Americans.

This release, catalog number SW-9034, was issued in stereo, allowing its gentle arrangements to stretch across living rooms in full-width sound. The wide stereo separation, an increasingly desirable feature in the early 1960s, made it particularly well suited to the emerging hi-fi market. In households where large, furniture-style entertainment units like the Magnavox Astro-Sonic were becoming centerpieces of the living room, records like Hawaiian Paradise played an important role in showcasing the stereo format’s potential. Sound could now move from one side of the room to the other, surrounding the listener in a way that monophonic recordings could never achieve.

This immersive experience was not simply an upgrade in fidelity, it was a form of theater. In the American living room of the mid-1960s, hi-fi furniture consoles like the Magnavox Astro-Sonic were not just machines, they were showpieces, wood-paneled monuments to modern living. The ad copy from a 1967 LIFE Magazine issue boasts of stereo so lifelike that it re-creates “the full beauty of music.” These systems were often placed in central family spaces, where their presence signified taste and a certain socioeconomic aspiration.

In that environment, a record like Hawaiian Paradise could shine. Its wide stereo mix allowed sound to stretch elegantly across the built-in speakers of these consoles, making the music feel present, tangible, and spatial. Tracks would drift from left to right, creating a sensation of immersion that was entirely new for the average listener. This wasn’t simply background music, it was designed to be demonstrated, to impress visitors and transport the household, even if just for an evening.

As a result, albums like this were curated experiences as much as they were musical collections. The stereo effect amplified the illusion of escape, lending a cinematic quality to otherwise modest productions. Hawaiian Paradise, with its pacing and imagery, was tailor-made for this context.

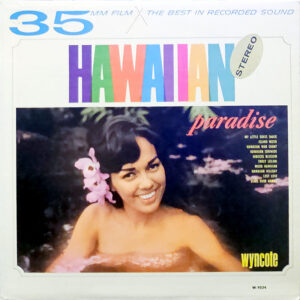

The record cover, with its vivid title lettering and serene image of a woman bathing in a natural spring, reinforces this escapist narrative. While minimal in detail, the visual elements on the sleeve were carefully chosen to transport the listener, promising not just a playlist but a portal.

From the first notes of “My Little Grass Shack,” it becomes apparent that this is not an ethnographic portrayal of Hawaiian music but rather a romanticized interpretation tailored for the mainland imagination. The album’s arrangements evoke images of patio parties, tiki bars, and resort-style leisure, enhanced by soft instrumentation and smooth transitions. As stereo technology became increasingly common in middle-class households, records like this one served to create atmosphere as much as to entertain. Listeners weren’t just playing songs,they were soundtracking an ideal.

Cataloged as SW-9034, the album’s packaging is minimal, with little to no information about the musicians or production details. However, the sequencing of tracks displays a deliberate sense of flow, allowing each piece to blend into the next. The mood, more than the individual songs, is what defines the record’s lasting appeal. In this sense, the LP becomes an auditory backdrop for an imagined vacation. Tracks like “Island Mood” and “Stars Over Hawaii” are designed less to be analyzed than to be absorbed, functioning like audio postcards from a place most listeners had never been.

Complementing the album’s carefully curated atmosphere is an intriguing technological detail noted prominently on the sleeve: the use of 35 millimeter magnetic film. Billed as “the best in recorded sound,” this format had been adapted from the motion picture industry and offered several advantages over standard magnetic tape. It allowed for an expanded recording surface, which in turn enhanced fidelity by significantly reducing background noise and improving signal clarity. For listeners accustomed to the subtle hiss of tape recordings, the result would have been notably more immersive.

The physical design of 35mm film, with its sprockets and consistent mechanical movement, offered additional benefits that audio engineers were eager to explore. Traditional tape could be susceptible to speed inconsistencies, causing fluctuations in pitch and timing. The film format largely eliminated these problems, providing steadier playback that allowed the warmth and texture of instruments, particularly the steel guitar and gentle percussion featured on this album, to be heard with greater nuance. Furthermore, the material’s thickness minimized the occurrence of print-through, a phenomenon where faint echoes of adjacent tracks would bleed into one another.

This method of recording, while expensive, aligned with the mid-century fascination with progress and innovation in consumer electronics. Whether or not every element of Hawaiian Paradise was captured using this technology, its promotion on the cover reflects a marketing strategy aimed at conveying quality through association. Wyncote’s willingness to gesture toward high fidelity, even as a budget label, suggests a deeper ambition to offer listeners not just an album, but an experience. In the context of 1960s domestic life, when hi-fi equipment became a fixture of leisure, these enhancements helped elevate background music into something closer to cinematic escapism.

Understanding how Hawaiian Paradise came to exist also requires a closer look at Wyncote’s place in the recording industry. The label was established in 1964 by Cameo-Parkway, a once-dominant force in American pop music. As musical trends shifted rapidly in the wake of the British Invasion, Cameo-Parkway faced declining sales and mounting competition. To maximize its existing assets, the company launched Wyncote as a budget imprint focused on reissues and theme-based collections.

Wyncote’s strategy emphasized wide distribution through nontraditional retail spaces including pharmacies, discount chains, and department stores. The formula was simple but effective: familiar songs, accessible price points, and visually appealing album art. Rather than market to collectors or audiophiles, Wyncote targeted casual listeners seeking ambient background music or novelty records. Its albums were designed to be impulse purchases, tucked into wire racks beside paperback novels and chewing gum.

Despite its pared-down production model, the label succeeded in placing music into households that might otherwise forgo record purchases. Albums like Hawaiian Paradise helped define a cultural soundscape where mood-driven listening became part of everyday life. Wyncote’s catalog, while often overlooked, stands as a document of its time, both in sound and strategy. Its releases may not have made headlines, but they made memories, often spinning in the background of dinners, parties, and quiet evenings at home.

As always, thanks for swimming along with me. I’m Finnley the Dolphin, and I couldn’t resist pulling this one out of the surf for a closer look. Records like Hawaiian Paradise may not carry the prestige of major-label releases, but they offer something just as valuable, a window into how everyday listeners experienced music in their homes, on their furniture-sized stereos, with the scent of dinner in the air and a vinyl escape spinning gently on the platter. Keep your ears open and your fins tuned, there’s always another treasure waiting to be rediscovered.

Sources:

Books

Dubowsky, Jack Curtis. Easy Listening and Film Scoring 1948–78. Taylor & Francis, 2021.

Magazines

“Magnavox Astro-Sonic.” LIFE, 29 Sept. 1967, p. 14.

“Billboard Magazine.” Billboard, 9 Dec. 1967, pp. 3, 8.

Websites

Discogs Contributors. “The Hawaiian Islanders – Hawaiian Paradise.” Discogs, https://www.discogs.com/release/23855618-The-Hawaiian-Islanders-Hawaiian-Paradise. Accessed 20 Apr. 2025.

Discogs Contributors. “The Hawaiian Islanders.” Discogs, https://www.discogs.com/artist/1057770-The-Hawaiian-Islanders. Accessed 20 Apr. 2025.

Finnley’s Audio Adventures. “Tropical Tunes and Technological Turns: The Story of Hawaiian Holiday.” Finnley’s Audio Adventures, 23 Mar. 2024, https://finnley.audio/2024/03/23/tropical-tunes-and-technological-turns-the-story-of-hawaiian-holiday/. Accessed 20 Apr. 2025.