Greetings, intrepid explorers of sound and story! Finnley the Dolphin here, inviting you to dive with me into the depths of a historical audio adventure that resonates beyond its melody. Today, we explore a unique artifact from the annals of children’s entertainment: “Let’s Help Mommy,” a record produced by The Children’s Record Guild. Yet, this tale is more than just about music; it’s a journey through a time of turbulence and tension in American history. So, take a breath, and let’s submerge into the past.

In the aftermath of World War II, as the world embarked on a journey of reconstruction and healing, a beacon of innovation emerged in the United States, specifically within the realm of children’s media. Young People’s Records, founded in 1946 by the visionary Horace Grenell. With a rich background as a producer, musician, teacher, and entrepreneur, Grenell was uniquely equipped to revolutionize children’s entertainment. This era marked the beginning of a significant shift, moving away from the fragile shellac records of the past to the more resilient and superior-sounding vinyl records, thereby enhancing the durability and audio quality of children’s storytelling and music.

Grenell’s innovation did not stop with the material transformation of records. He envisioned a holistic approach, creating content that was as educational as it was entertaining. Young People’s Records aimed to fill post-war American homes with diverse stories and songs, fostering children’s imaginations and promoting values such as cooperation and friendship—principles resonant with families navigating the era’s challenges.

The initiative’s success and the changing retail landscape led to the evolution of Young People’s Records into The Children’s Record Guild. This transition expanded the organization’s reach, allowing a wider audience to access its valuable content through different distribution channels, including partnerships like the one with the Book-of-the-Month Club. The Children’s Record Guild continued the mission initiated by Young People’s Records, serving as a pivotal source of educational content in the pre-digital age.

However, the journey of these groundbreaking ventures was not infinite. Young People’s Records, having illuminated the paths of countless children from 1946, concluded its mail-order subscription service in 1957, transitioning fully to The Children’s Record Guild. This transformation marked a significant turning point in the distribution and accessibility of children’s audio content. The Guild adopted a subscription-based model, reminiscent of the popular Book-of-the-Month Club, which allowed it to sail directly into the homes of eager young listeners across the nation. This direct mail-order system not only broadened its reach but also ensured that a steady stream of musical narratives and educational tales found their way into family life, fostering a love for learning and listening.

However, beneath the calm surface of these noble ventures, a tempest was stirring. The Cold War period was steeped in a pervasive climate of fear and mistrust, with the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) orchestrating a national crusade to root out and expose communist influences. It was within this fraught environment that Young People’s Records and its subsequent incarnation, The Children’s Record Guild, found themselves caught in the crosshairs of political scrutiny.

These organizations, despite their focus on educational content and commitment to apolitical storytelling, were inexplicably branded as “subversive” entities in an array of governmental documents. This unjust classification cast a long, dark shadow over their valuable contributions to the realm of children’s entertainment. The root of these allegations lay in supposed associations and underlying ideologies that, through the distorted lens of HUAC, seemed to smear their creative efforts with the stain of communism.

At the vortex of this political whirlwind was Horace Grenell, the visionary architect of these musical and narrative journeys. Summoned to stand before the HUAC, Grenell was thrust into an unwelcome spotlight, facing a barrage of accusations and insinuations. In this high-stakes scenario, he resorted to invoking the 1st and 5th Amendments, a move to protect his personal liberties and to stand firm against what he perceived as unwarranted intrusion and baseless allegations. This bold stance, while safeguarding his own principles, ignited further controversy and stoked the fires of suspicion that were rampant during this period of American history. It highlighted a profound conflict between individual freedoms and the pervasive atmosphere of national paranoia that defined the McCarthy era.

The impact of this confrontation was profound, not just for Grenell and his associates, but also for the broader landscape of children’s media. The labels of subversion and the taint of political intrigue threatened to undermine the very essence of what Young People’s Records and The Children’s Record Guild aimed to achieve: to educate, entertain, and inspire young minds free from the shadows of ideological warfare. This chapter in their history illustrates a significant moment where cultural contributions were jeopardized by the chilling effects of political fearmongering.

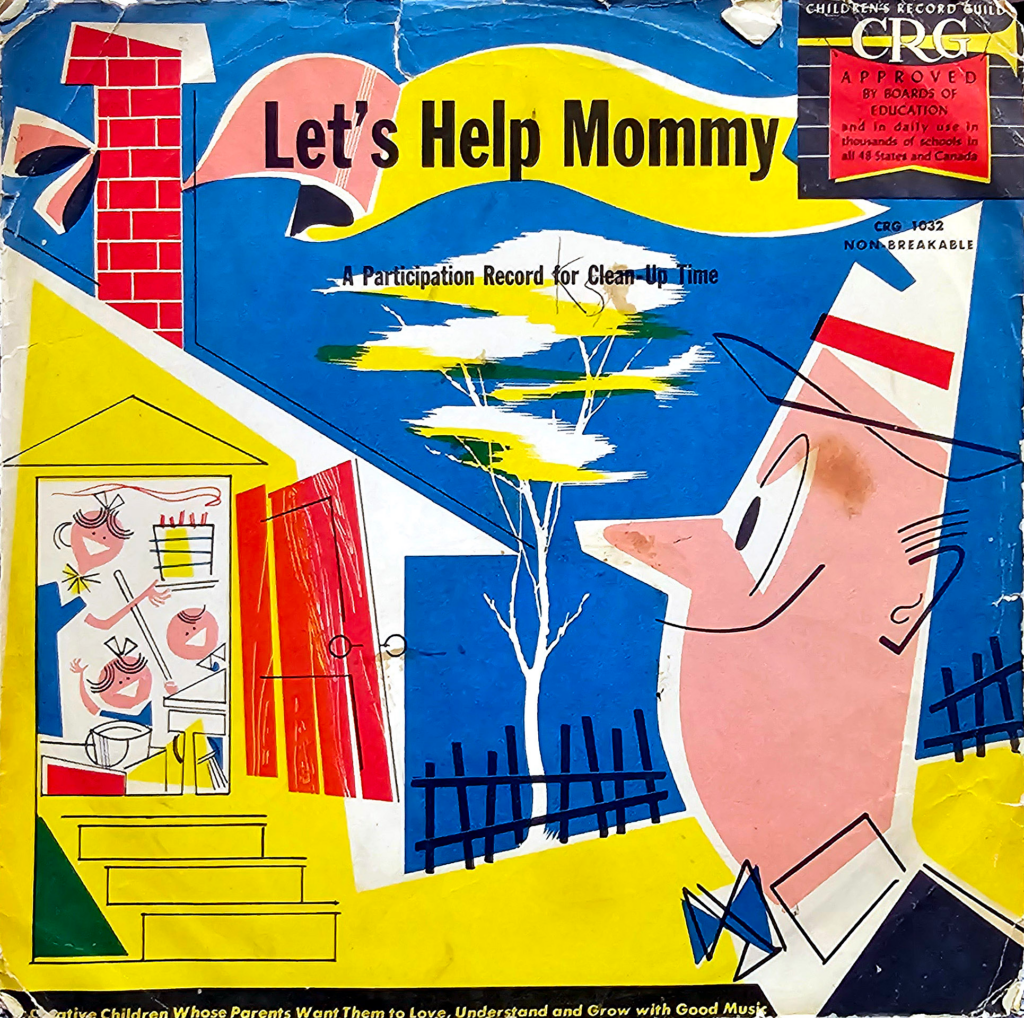

In the vibrant anthology of The Children’s Record Guild, “Let’s Help Mommy” emerged as a an auditory beacon of familial cooperation and childhood involvement. This record transcended its physical form, becoming a pivotal educational tool that leveraged the power of storytelling to instill values of responsibility and altruism in its young audience.

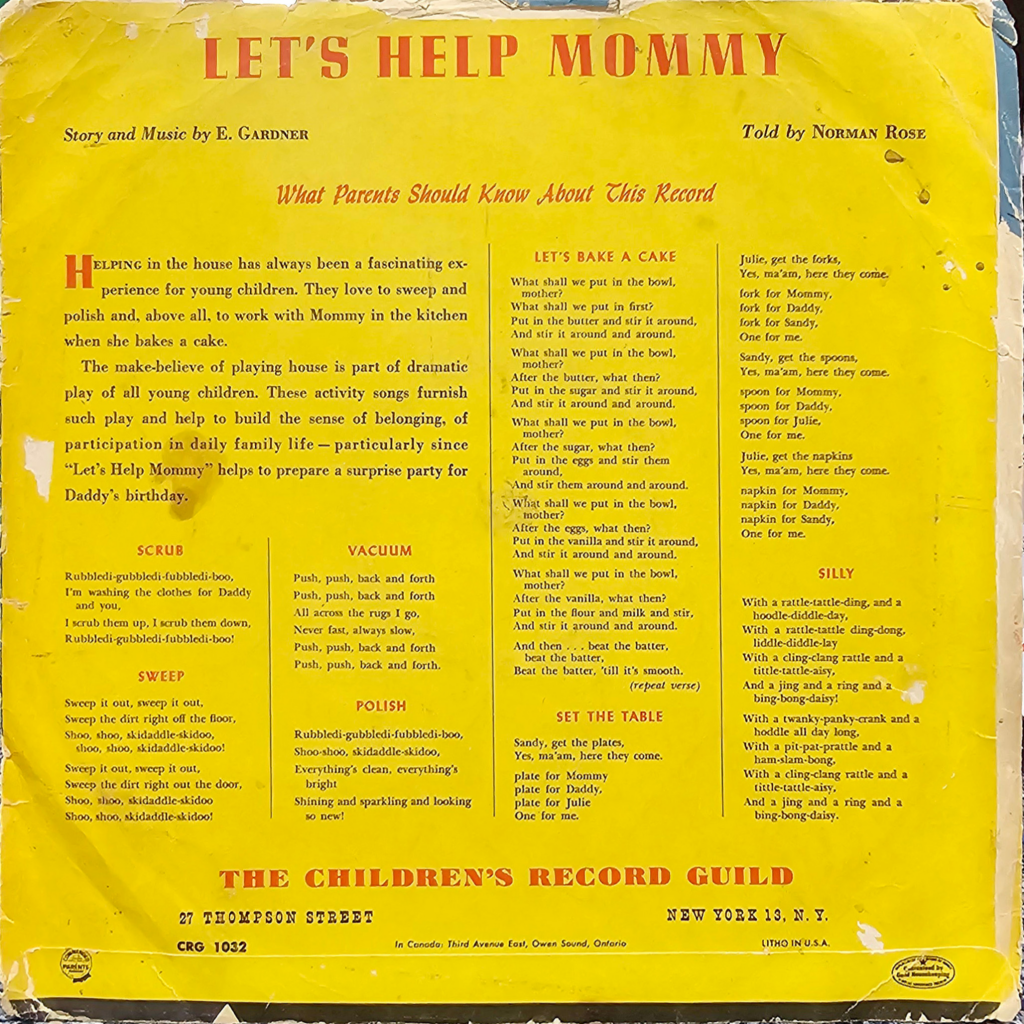

The narrative of “Let’s Help Mommy” was meticulously crafted, weaving together everyday scenarios that mirrored the listeners’ own lives. The stories unfolded in a familiar domestic setting, where children were not just passive inhabitants but active participants. The songs and story served as a gentle nudge towards self-reliance, encouraging little ones to embrace tasks such as tidying up, setting the table, or assisting with simple household chores. This immersive approach transformed listeners into characters of their own life stories, instilling a sense of pride and accomplishment in contributing to their family’s well-being.

Amplifying the record’s educational value was the distinctive voice of Norman Rose, whose baritone timbre resonated with authority and warmth. Known affectionately as “the Voice of God,” Rose had an exceptional talent for storytelling, his intonations rich with empathy and wisdom. His voice, familiar to many from his roles in radio dramas and narrations, lent a sense of gravitas to the narrative, making “Let’s Help Mommy” a memorable and engaging experience for children and parents alike.

Rose’s narration went beyond mere reading; it was an invitation to journey through the day’s activities with a sense of purpose and joy. His ability to convey complex emotions and lessons in an accessible manner helped children understand the value of their contributions within the home. The interactive storytelling, combined with Rose’s guiding voice, created an environment where learning was not a chore but a delightful adventure.

As we ascend from the historical depths of “Let’s Help Mommy” and the narratives woven by The Children’s Record Guild, we carry with us not only a story of innovation and educational ambition but also a cautionary tale of creativity under siege. This journey through time sheds light on the fragility of artistic and educational endeavors in the face of political extremism, a theme as relevant in the era of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) as it is in today’s climate of book bans and cultural censorship.

The creation of “Let’s Help Mommy,” a beacon of innocence and familial cooperation, stands as a testament to what can flourish in an environment of freedom and support. Yet, this narrative jewel could have remained buried in the sands of history had the HUAC’s efforts succeeded in silencing the creative voices behind Young People’s Records and The Children’s Record Guild. The record’s existence reminds us of the thin line between expression and suppression, a line that individuals like Horace Grenell dared to defend, even in the face of potential personal and professional oblivion.

Drawing parallels to our current times, we find ourselves once again navigating turbulent waters where educational materials and books face bans and restrictions, fueled by a new wave of cultural and political extremism. Just as the HUAC sought to uproot perceived subversive elements from the fabric of American society, today’s movements aim to excise diverse voices and perspectives from public discourse and education, threatening the richness of our collective understanding and experience.

In this mirrored struggle, “Let’s Help Mommy” becomes more than a record; it evolves into a symbol of resilience against the forces that seek to homogenize and control cultural and educational content. It serves as a reminder that the stories we allow into the lives of our children can shape their understanding of the world and themselves. The banning or suppression of educational materials, whether under the guise of anti-communism yesterday or the banner of protecting sensibilities today, erodes the foundation of free thought and inquiry that underpins a vibrant, evolving society.

As we reflect on this parallel, it becomes evident that the battles fought by Grenell and his contemporaries are not relics of the past but ongoing challenges to be met with vigilance and courage. “Let’s Help Mommy” and its journey through the annals of history encourage us to consider the value of diverse narratives and the importance of safeguarding the avenues through which they reach our future generations.

In closing, as we swim forward from the shadowy depths of censorship into the light of understanding and acceptance, let’s carry the spirit of “Let’s Help Mommy” with us. Let this record, born from a time of conflict, and preserved through decades of change, inspire us to advocate for a world where all voices are heard and valued. Let’s commit to ensuring that the lessons of cooperation, kindness, and family unity it embodies are not lost in the currents of time but are shared, celebrated, and expanded upon.

Thank you, dear adventurers, for joining me, Finnley, on this reflective journey. As we continue to navigate the vast ocean of stories and history, let us remain ever vigilant, ever curious, and ever kind, championing a future where every story has a place, and every voice can sing.

Until we meet again, keep your fins steady and your hearts open, as we dive into the endless sea of knowledge and empathy that binds us all.

Sources:

https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/nmah_1320730

http://davelindastourdefrance.blogspot.com/2007/12/horace-grennell.html

https://music.metason.net/artistinfo?name=Horace+Grenell

https://ia902808.us.archive.org/1/items/CommunismHypnotismAndTheBeatles/CommunismHypnotismAndTheBeatles_text.pdf (p. 18-19)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Norman_Rose

https://www.discogs.com/release/6520930-Norman-Rose-Lets-Help-Mommy