Hello my shiny shelled friends. Finnley the Dolphin here, gliding in from the deep with another sonic treasure from the tide pools of yesterday. Today we are exploring a trio of recordings that all share one remarkable invention. The Sonovox. This little device sat against a performer’s throat and turned ordinary speech into something wonderfully strange. It gave trains a voice, turned airplanes into chatty characters, and even helped guide young listeners through imaginary orchestras. So grab your flippers, adjust your stylus, and join me as we follow these talking machines across three very different shores.

The Sonovox entered public awareness in 1939 when Gilbert Wright demonstrated a new method of shaping sound through the human throat. The device used a pair of small transducers placed against the sides of the neck, which caused the throat to vibrate in response to prerecorded sounds. These vibrations allowed the performer to form words with their mouth while the transducers supplied the tonal content. The result created speech without the use of the performer’s vocal cords, which fascinated audiences who had never encountered this method of sound production. Early demonstrations often highlighted its unusual timbre, which appeared to turn inanimate objects into speaking characters. Public imagination quickly attached itself to the novelty of the device, and Wright’s company began marketing it as a specialized tool for entertainment and advertising.

The Wright-Sonovox company operated as an affiliate of the Free and Peters advertising agency, which provided the device with a direct path into commercial media. Advertisers immediately saw the potential for speaking trains, talking appliances, and other character-driven promotional material. The ability to create a voice that felt both mechanical and human offered producers a new way to capture attention during the rapid expansion of spot advertising. Radio stations also adopted the Sonovox for station identifiers, where its distinctive sound created a recognizable signature for listeners. Companies such as PAMS and JAM Creative Productions produced many of these station IDs, which circulated widely across American broadcast markets. Through this commercial presence, the Sonovox entered daily life in a way few experimental audio devices had previously achieved.

Film studios began using the Sonovox shortly after its debut. One of the earliest known uses occurred in a Pathé Newsreel that featured a demonstration with Lucille Ball during her early Hollywood years. The device made additional appearances in films during 1940 and 1941, which helped to normalize its presence in mainstream entertainment. Ernst Toch’s score for the 1940 film The Ghost Breakers included Sonovox elements that blended with orchestral material. Audiences also encountered it in You’ll Find Out, where the device received an opening credit “Special Sound and Musical Effects by Sonovox” for creating the spectral voices central to several scenes. These early productions helped to anchor the Sonovox in cinematic history before its later decline in popularity.

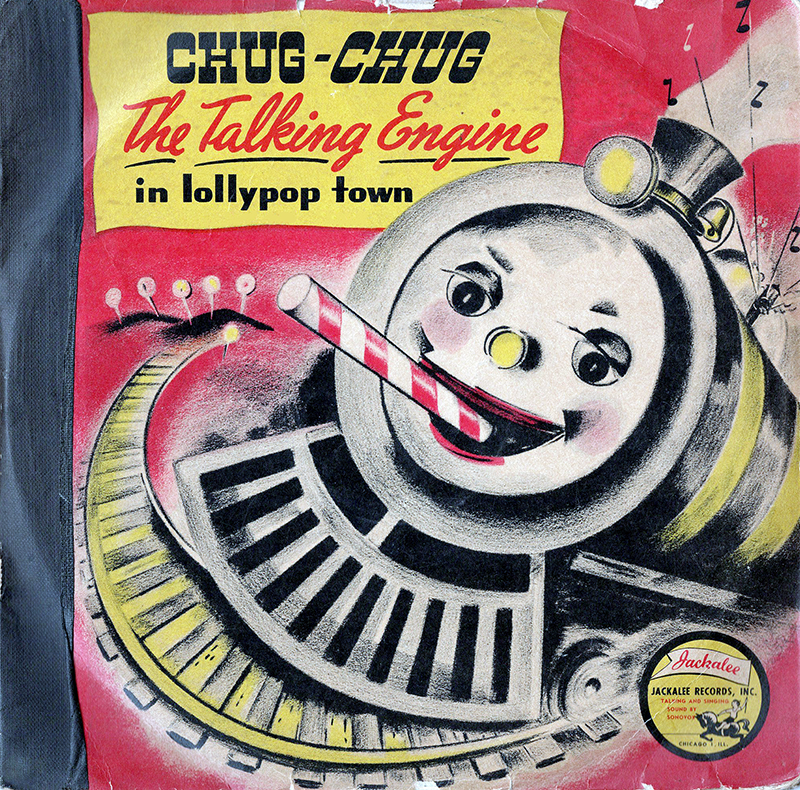

Jackalee Records used the Sonovox as a signature gimmick, beginning with Chug Chug the Talking Engine in 1947. These releases formed a short lived series that highlighted mechanical characters brought to life through throat shaped electronic voices. The company was led by J. M. Gleason, who also served as the manager of Chicago Wright Sonovox. Jackalee’s staff included Leslie J. Walker from Wright Sonovox and Gus Haganah from Standard Radio. Their involvement shows how closely these productions were linked to the device’s developers. Chug Chug the Talking Engine was released as both a single disc album and a two disc set, each packaged in bright, train themed artwork meant to appeal to young listeners. The record used Sonovox effects for the engine’s speech and featured storytelling in a light, whimsical tone. Although production credits were not always clearly listed on children’s albums from this period, surviving materials show that the team intended the Sonovox itself to be the star attraction.

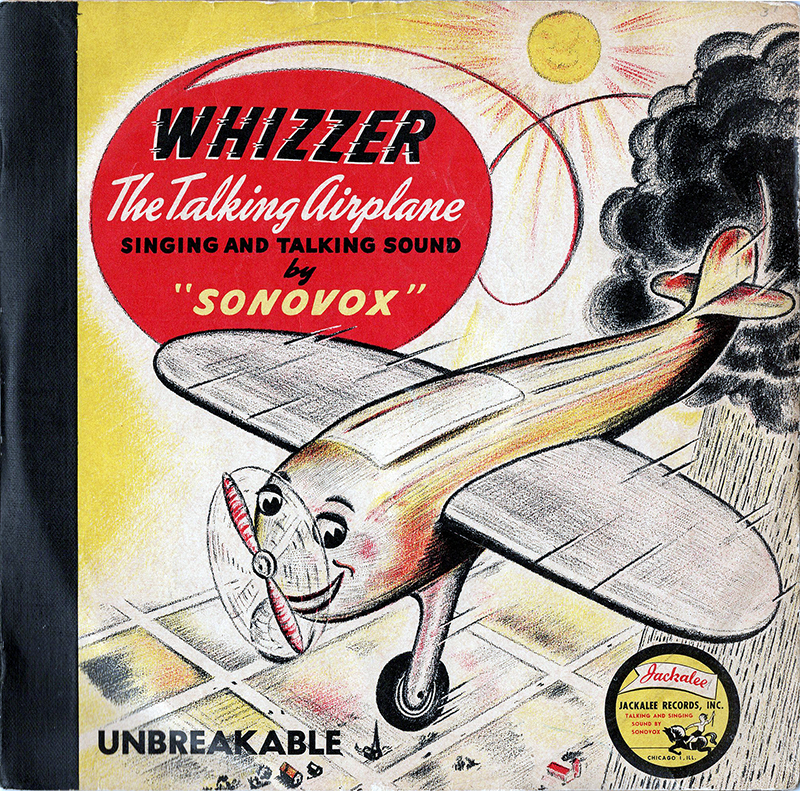

Jackalee followed with Whizzer the Talking Airplane, also in 1947, and this time the company leaned fully into its signature device. The record sleeve proudly credited the performance to Sonovox, treating the device as a featured vocalist. The album came as a two disc, ten inch, red shellac set with four continuous parts. The packaging showed a stylized red airplane with expressive facial features, which mirrored the way the Sonovox shaped the voice into cheerful mechanical speech. Matrix markings identify the discs as W 1333, confirming Jackalee’s internal catalog system. Like the earlier Chug Chug releases, Whizzer presented an adventure driven story where the talking vehicle guided the listener through a series of short narrative scenes. The album’s production credits again tie to the same Chicago based team responsible for earlier Sonovox promotions, which suggests the record was part of a focused effort to position the device as a new form of children’s entertainment.

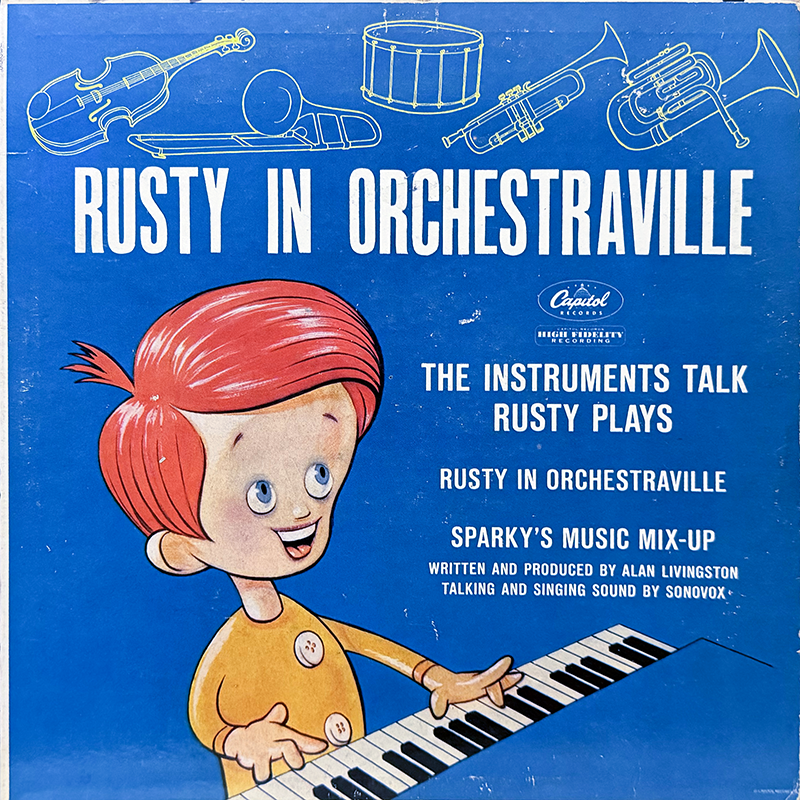

Rusty in Orchestraville arrived later and connected the Sonovox to a different style of storytelling. This 1962 Capitol Records release combined spoken narration, orchestral music, and electronic voice effects. Unlike Jackalee’s earlier railroad and aviation themes, Rusty centered on a child’s introduction to musical instruments and the structure of an orchestra. The project included work from writer and producer Alan Livingston, who played a central role in many Capitol children’s releases and created characters such as Bozo the Clown. Livingston later became a major executive at Capitol and was instrumental in the company’s transition into the 1960s. His experience with children’s media helped shape Rusty’s narrative tone and kept the focus on musical discovery.

The record featured Henry Blair as a primary voice actor. Blair had a strong background in radio and film and was known for his ability to portray youthful characters with emotional clarity. He appeared in a number of mid century broadcasts that helped establish him as a dependable narrator for family oriented productions. His work on Rusty in Orchestraville gave the album a light and welcoming presentation that supported both spoken segments and musical instruction.

Billy Bletcher also contributed to the production and brought a long history in animation, radio, and comedic acting. He voiced Pete in the Mickey Mouse series and the Big Bad Wolf in the Disney Three Little Pigs films. For MGM he played Spike the Bulldog and provided additional voices in the Tom and Jerry shorts. His work for Warner Bros included Papa Bear in the Three Bears cartoons directed by Chuck Jones along with many additional roles across the studio’s output. He also voiced Don Del Oro in the 1939 serial Zorro’s Fighting Legion. Bletcher’s theatrical delivery and expressive range offered Rusty a sense of character driven humor that worked well with the Sonovox sequences.

The album’s music was composed by Billy May, who brought extensive experience as an arranger and bandleader. He arranged major Capitol albums for Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole, Ella Fitzgerald, Peggy Lee, Mel Tormé, and many other artists whose work defined mid century popular music. His projects extended into television and film, where he composed for titles such as The Green Hornet, The Mod Squad, Naked City, and The Front Page. He also contributed arrangements for Disney related material and participated in studio sessions involving reinterpretations of Disney stories. May’s orchestral skill allowed the musical sections of Rusty in Orchestraville to function as instructional material while still serving the flow of the narrative. His writing gave the Sonovox passages enough space to stand out without overwhelming the story.

Taken together, these three records show how the Sonovox shaped children’s audio during different decades. Chug Chug presented the novelty of a talking train for the first time. Whizzer carried the idea further by crediting the device as a performer. Rusty applied the technique within a more structured educational setting supported by established songwriters, narrators, and composers. Each project reflected a different approach to early electronic voice effects and offered listeners something that did not sound like ordinary speech or typical puppetry. This range shows how flexible the technology could be when paired with creative teams willing to explore new ideas.

And that brings us back to the present tide. Finnley the Dolphin signing off with a grateful flip of the fins. These talking machines may come from another time, but their voices still echo across the currents. If you enjoyed our dive into the world of the Sonovox, keep your ears tuned and your shells polished. There are always more forgotten voices waiting just below the surface.

Sources:

Alan Livingston. Discogs, https://www.discogs.com/artist/597022-Alan-Livingston.

Tom Reddy. Discogs, https://www.discogs.com/artist/2462382-Tom-Reddy.

“Billy May.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Billy_May.

Billy May. Discogs, https://www.discogs.com/artist/254886-Billy-May.

“Billy Bletcher.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Billy_Bletcher.

Billy Bletcher. Discogs, https://www.discogs.com/artist/310232-Billy-Bletcher.

Henry Blair. Discogs, https://www.discogs.com/artist/1020855-Henry-Blair.

“Talk Box: Sonovox.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Talk_box#Sonovox.

“Chug Chug Talking Engine in Lollipop Town.” WorthPoint, https://www.worthpoint.com/worthopedia/chug-chug-talking-engine-lollipop-4916041778.

Sonovox. “Chug Chug In Lollypop Town.” Discogs, https://www.discogs.com/label/1762606-Jackalee-Records-Inc.

Sonovox. “Whizzer the Talking Airplane.” Discogs, https://www.discogs.com/release/14742413-Sonovox-Whizzer-The-Talking-Airplane.

Record Retailing Yearbook and Directory. M. & N. Harrison, 1948.

Tompkins, Dave. How to Wreck a Nice Beach: The Vocoder from World War II to Hip-Hop, The Machine Speaks. Melville House, 2011, pp. 130–131.

The Craft of Criticism: Critical Media Studies in Practice. Taylor & Francis, 2018, pp. 79–82.

Reddell, Trace. The Sound of Things to Come: An Audible History of the Science Fiction Film. University of Minnesota Press, 2018, pp. 3–4.

“New Companies and Changes.” Record Industry, May 1947, pp. 17–18.

“Jackalee Records Launches ‘Chug-Chug.’” Broadcasting, 5 May 1947, p. 62.

Henry Blair and Billy Bletcher. “Rusty in Orchestraville.” Discogs, https://www.discogs.com/release/3205429-Henry-Blair-And-Billy-Bletcher-Rusty-In-Orchestraville