Ahoy, sound seekers! It’s your vinyl-loving, wave-riding host Finnley the Dolphin here with another deep dive from the treasure chest of forgotten audio gems. Today, we’re flipping open the shell on a piece of educational gold: Miss Frances Presents Ding Dong School. This 1959 LP might look simple, but it holds the echoes of a transformative time in children’s broadcasting. Back then, records were not just for dancing. They were for learning, too.

If you’ve ever wondered what it sounded like to grow up with a calm, caring adult guiding your imagination through song, play, and gentle curiosity, this record is your time machine. With Miss Frances at the helm and the Sandpiper Chorus & Orchestra keeping tempo, this isn’t just another vintage children’s album. It’s an audio classroom, pressed into wax and sealed with intention.

In this blog entry, we’ll trace the currents that shaped children’s TV in the 1950s. We’ll explore the remarkable story of Dr. Frances Horwich, better known as Miss Frances. Then we’ll crack open the grooves of the Ding Dong School record itself, all the way to its final lullaby.

By the early 1950s, American television was undergoing an explosive growth in both reach and cultural influence. As television sets became household fixtures, networks and advertisers quickly turned their attention to younger audiences. Programming for children was still in its infancy, shaped more by experimentation and sponsorship opportunities than any cohesive philosophy of education. Nonetheless, the decade saw the launch of some of the most enduring figures in children’s media, many of whom would leave a lasting impact on the industry and its viewers.

Children’s television in this period was marked by a tension between entertainment and education. While shows like “Captain Video” and “Howdy Doody” leaned into slapstick, puppetry, and serialized fantasy, others sought to bring structure and learning into the living room. NBC, CBS, and ABC each experimented with weekday morning and weekend time slots, testing the waters for educational content. Often, the educational programs were aired in less competitive time blocks, assuming lower advertising revenues. Yet, these experiments set the foundation for what would later become public television’s mission: to instruct and inspire.

Among the earliest successful attempts to reach children through a pedagogical lens was “Ding Dong School,” which debuted on NBC in 1952. Created by educator Dr. Frances Horwich, the program stood apart for its radical simplicity and emotional intelligence. Instead of frenetic action or fantastical storytelling, it presented a calm, engaging adult speaking directly to the viewer. This approach would be echoed decades later by Fred Rogers.

Children’s programming in the 1950s also benefited from broader cultural forces. The postwar baby boom created a massive child audience, and progressive educational theories emphasized early development and structured play. The era’s shows often reflected the social values of the time: obedience, hygiene, patriotism, and curiosity. Within this context, programs that addressed children as thinkers and individuals rather than mere consumers felt revolutionary.

Even as the decade closed, the question lingered: could television be more than a distraction for children? As advertising dollars leaned toward cartoons and toy-sponsored content, educators and producers like Dr. Frances Horwich stood at the intersection of commerce and conscience. They made the case that a child’s time in front of a screen could be meaningful if handled with care, intention, and respect.

Dr. Frances Rappaport Horwich, affectionately known to millions as “Miss Frances,” was not just a television personality. She was a deeply principled educator who brought her doctoral training and classroom experience to the screen. Frances Horwich, originally from Ottawa, Ohio, pursued advanced studies in education, completing a master’s degree at Columbia and a doctorate at Northwestern. Before entering the world of broadcasting, she dedicated herself to teaching and curriculum development. Her career in education shaped her belief that young children deserved thoughtful, nurturing instruction. When the opportunity to appear on television arose, she saw it not as a chance for personal fame but as a new avenue to support childhood development. Her goal was to bring the classroom’s integrity into a medium that reached millions of homes.

In 1952, Horwich launched “Ding Dong School” on NBC, transforming daytime television with a revolutionary concept: a quiet, nurturing adult speaking directly to preschool children through the camera lens. Unlike frenetic hosts of other programs, Miss Frances slowed things down. She guided children through finger painting, storytelling, stretching, and thoughtful observation. She invited them to think, not just watch. And critically, she did this while maintaining full creative control, owning the rights to her show, which was a rare feat in television history.

Horwich’s influence extended far beyond television. As her show gained popularity, she became a nationally respected advocate for educational programming. In 1954, NBC named her Head of Children’s Programming, a role in which she sought to raise the bar for all youth content. But when NBC canceled “Ding Dong School” in 1956 to make room for “The Price is Right,” Horwich resigned in protest. She would go on to syndicate her program independently until 1965, proving her belief that ethics in children’s media were more important than prime-time profits.

Parallel to her TV career, Horwich became a prolific author. She penned over 27 children’s books tied to the show, as well as two titles aimed at parents. These ranged from activity books and coloring rolls to structured storybooks, all designed with the same care and intention as her on-screen lessons. Brands like Whitman and Rand McNally published her work, often using her image and reputation to reinforce trust with parents.

Her commitment to children extended into her personal life. Though she had no children of her own, Horwich viewed her young viewers with maternal affection and professional responsibility. She famously refused to advertise toys she found violent or age-inappropriate and declined endorsements unless she believed in the educational value of the product. In 2001, months before her death, she was inducted into the Silver Circle by the Chicago Chapter of the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences in recognition of a life spent advocating for children with quiet grace.

Ding Dong School on Record: Golden Sound for Golden Minds

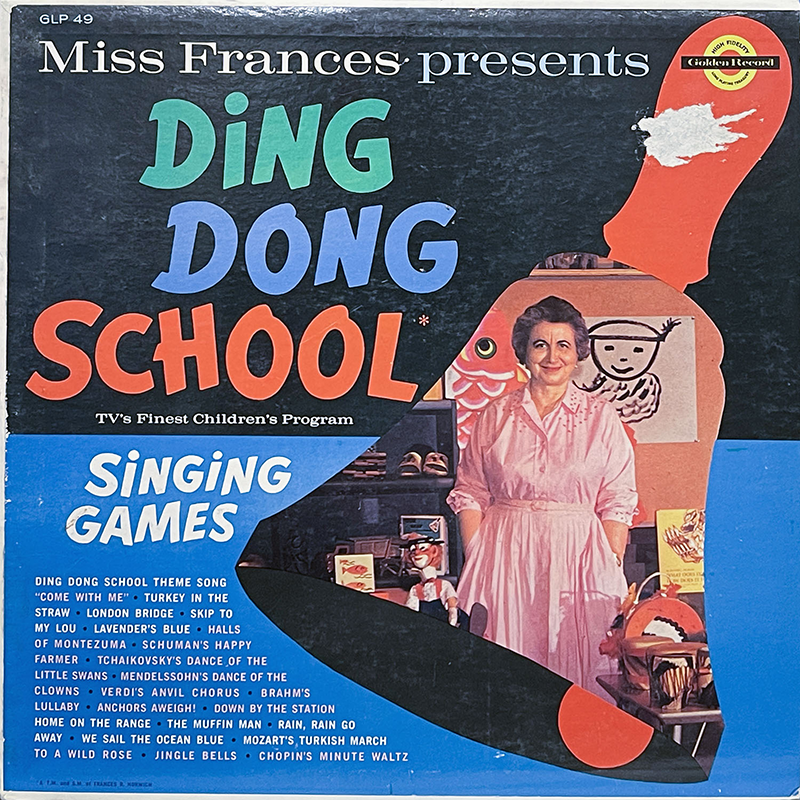

In 1959, as part of the expanding “Ding Dong School” brand, Golden Records released a vinyl LP titled Miss Frances Presents Ding Dong School (GLP-49). More than a mere merchandising spin-off, the album served as an auditory extension of the show’s principles. It brought the spirit of Miss Frances into homes in a new format: portable, repeatable, and musical. For many children, this record was their first introduction to classical motifs, folk traditions, and educational songs wrapped in warmth and familiarity.

The record was a collaboration between trusted names in children’s entertainment. The music was directed by Jimmy Carroll, a respected arranger who had worked with Mitch Miller and others, and featured performances by The Sandpiper Chorus and Orchestra. The album was produced by Hudson Productions and distributed by Golden Records, a leading label in children’s music during the 1950s and 1960s. Golden Records was known for its child-friendly LPs and collaborations with icons like Captain Kangaroo and Shari Lewis.

The album included a curated blend of American folk songs, nursery rhymes, and light classical pieces. Selections such as “Lavender’s Blue,” “The Muffin Man,” and “Home on the Range” were paired with more sophisticated fare like Tchaikovsky’s “Dance of the Little Swans” and Mozart’s “Turkish March.” Even Chopin’s “Minute Waltz” made an appearance, offering young ears a gentle entry into the world of classical music. True to form, Miss Frances provided introductions and guidance throughout, reinforcing the program’s central idea: music and play are both vehicles for learning.

This LP also served as a marketing bridge, supporting Frances Horwich’s broader ecosystem of books, games, and television. Ads in LIFE magazine positioned the album as both entertainment and parenting tool. It was priced accessibly at $1.98 and marketed as “TV’s Finest Children’s Program” in audio form. Parents were promised wholesome, repeatable fun and a few minutes of peace and quiet.

**Full Track Listing for GLP 49

A1. Ding Dong Theme Song “Come With Me”

A2. Halls Of Montezuma

A3. Lavender’s Blue

A4. Turkey In The Straw

A5. Anvil Chorus

A6. Dance Of The Swans

A7. Schuman’s Happy Farmer

A8. Brahms’ Lullaby

A9. Dance Of The Clowns

A10. Anchors Aweigh

A11. To A Wild Rose

B1. Home On The Range

B2. The Muffin Man

B3. London Bridge

B4. Rain Rain Go Away

B5. We Sail The Ocean Blue

B6. Skip To My Lou

B7. Mozart’s Turkish March

B8. Down By The Station

B9. Chopin’s Minute Waltz

B10. Jingle Bells

From the depths of the analog sea to the turntables of memory, Miss Frances Presents Ding Dong School is a shining pearl of mid-century media. As I swam through its cheerful melodies and structured calm, I could almost hear the quiet hum of a classroom wrapped in vinyl. This record does more than preserve a time. It teaches us something enduring about care, consistency, and the rhythm of thoughtful instruction.

For fans of educational ephemera, this LP is more than a collectible. It’s a glimpse into a world where even play had purpose, where producers trusted that children could appreciate Brahms as much as they did “The Muffin Man.” Miss Frances didn’t just speak to kids. She respected them, and that respect ripples through every track.

As always, thanks for paddling along with me. If you enjoyed this exploration, be sure to surface again soon. There are plenty more sonic shipwrecks and auditory oddities waiting in the archive. Until next time, keep your fins on the vinyl and your ears tuned to the past.

Yours in sound,

Finnley the Dolphin

🎧 Full blog post and archive:

https://www.finnleysaudioadventures.com

💬 Join the conversation:

https://bsky.app/profile/finnley.audio

💖 Support the archive:

https://ko-fi.com/finnleysaudioadventures

📺 Subscribe for more:

https://www.youtube.com/@FinnleysAudioAdventures

Sources:

Books

Chudacoff, Howard P. Children at Play: An American History. NYU Press, 2008, p. 205.

Terrace, Vincent. Encyclopedia of Television Subjects, Themes and Settings. McFarland, 2024, p. 71.

Magazines

“Ding Dong School.” LIFE, 16 Mar. 1953, pp. 123–124, 126.

“Miss Frances’ All-Day-Long Book.” LIFE, 22 Nov. 1954, p. 170.

Trade Publications

“Miss Frances’ Ding Dong School Series.” The Publishers Weekly, vol. 164, 1953, p. 370.

“Character Licensing in School Supplies.” Playthings, vol. 60, no. 9, Sept. 1962, p. 125.

Government Documents

United States, Congress, Senate, Committee on Commerce. Hearings on Network Practices in Television Broadcasting, 20 June 1956. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1957, pp. 2707–2708.

Audio Recordings

Miss Frances and The Sandpiper Chorus & Orchestra. Miss Frances Presents Ding Dong School. Golden Records, 1959. LP.

Web Sources

“Dr. Frances Horwich.” Discogs, https://www.discogs.com/artist/3903902-Dr-Frances-Horwich.

“Miss Frances Presents Ding Dong School.” Discogs, https://www.discogs.com/release/8025571-Miss-Frances-And-The-Sandpiper-Chorus-Orchestra-Miss-Frances-Presents-Ding-Dong-School.

“Golden Records (2) – Label.” Discogs, https://www.discogs.com/label/100354-Golden-Records-2.

“Frances Horwich Biography.” IMDb, https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0395837/bio.

“Jimmy Carroll Biography.” IMDb, https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0140862/bio.

“Mitch Miller Biography.” IMDb, https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0589022/bio.