Greetings, audio adventurers! It’s Finnley the Dolphin here, ready to dive into another fascinating chapter of sound and motion history. Today, we’re setting our sights on the enchanting world of early animation technology, where we explore how a 19th-century invention paved the way for one of the most delightful children’s toys of the mid-20th century: the Red Raven Movie Records. From the brilliance of Charles-Émile Reynaud’s praxinoscope to the magical blend of music and motion that captivated kids in the 1950s, this blog post will take you on a journey through the evolution of motion picture technology and its lasting impact on entertainment. So, grab your snorkels and get ready to explore the waves of innovation that made these records a beloved part of childhood!

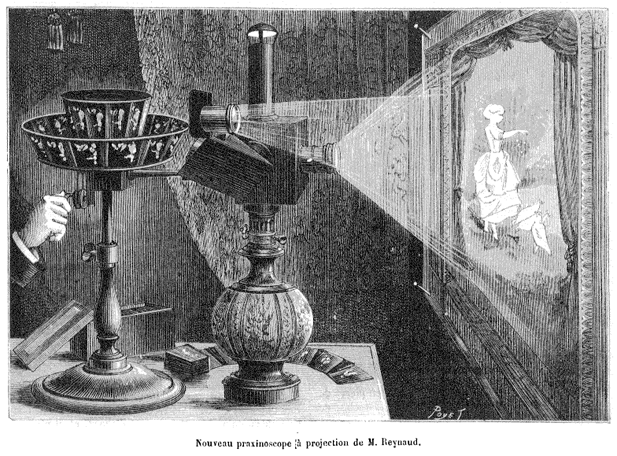

The evolution of motion picture technology is a fascinating journey that began with simple yet ingenious devices, one of which was the praxinoscope. Invented in 1877 by Frenchman Charles-Émile Reynaud, the praxinoscope represented a significant advancement over its predecessor, the zoetrope. While both devices utilized a series of images arranged around the inner surface of a spinning cylinder to create the illusion of motion, the praxinoscope introduced a critical innovation: an inner circle of mirrors. These mirrors allowed for a brighter, clearer, and less distorted image, providing viewers with a smoother and more immersive experience.

Reynaud continued to refine his invention, leading to the creation of the Praxinoscope-Théâtre in 1879, which added theatrical elements to the viewing experience. This version was housed in a box that revealed only the moving figures against an interchangeable backdrop, further enhancing the illusion of motion within a narrative setting. The praxinoscope even saw variations that included projection capabilities, allowing images to be displayed on a screen for larger audiences—a precursor to modern cinema.

By the late 19th century, the praxinoscope had inspired several other inventors and manufacturers, including Ernst Plank of Germany, who created versions powered by miniature hot air engines. Despite its early popularity, the praxinoscope was eventually overshadowed by the advent of photographic film projectors, such as those developed by the Lumière brothers.

Birmingham Museums Trust

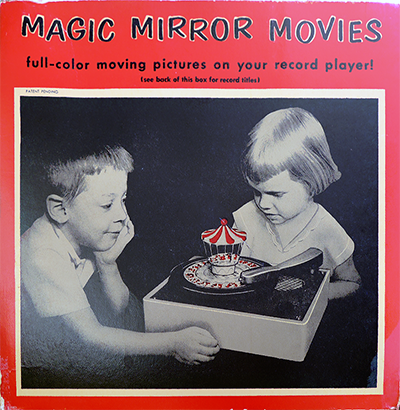

However, the concept behind the praxinoscope experienced a revival in the mid-20th century with the introduction of the Red Raven Movie Records in 1956. This innovation brought the praxinoscope into the world of children’s entertainment, combining it with the phonograph. The Red Raven Magic Mirror was a sixteen-sided praxinoscopic reflector that was placed over the spindle of a record player. As a specially designed 78 rpm record played, the Magic Mirror rotated along with it, reflecting an animated scene that corresponded with the song being played. This captivating blend of sound and motion delighted children, bringing Reynaud’s 19th-century invention into a new era.

The Red Raven system found success not only in the United States but also internationally, with adaptations appearing in Europe and Japan under various names. This 20th-century adaptation of the praxinoscope serves as a testament to the enduring appeal of early motion picture technology and its ability to captivate audiences across generations.

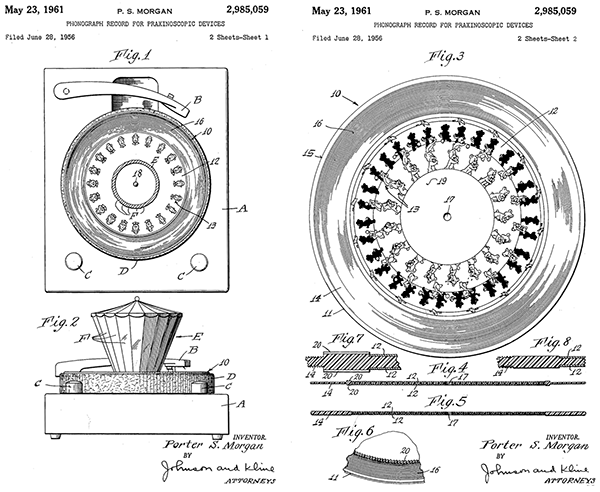

One significant step in this evolution occurred when Porter S. Morgan filed a patent application in 1954 for a device designed to entertain children using phonographs. The invention involved a disc with sound recordings and a series of painted pictures that, when played on a phonograph, would reflect in a polygonal drum of mirrors. As the record spun, the mirrors would create a moving image, much like the early motion pictures. However, the Patent Office initially rejected Morgan’s application, arguing that the invention was merely an obvious extension of prior art, such as the praxinoscope and other similar devices.

PHONOGRAPH RECORD FOR PRAXINOSCOPIC DEVICES

The case, Morgan Development Laboratories, Inc. v. Commissioner of Patents, was brought before the court, where the judge ultimately ruled in favor of Morgan, stating that his invention represented a novel combination of sound and image that was not obvious to those skilled in the art. This decision cleared the way for the patenting and commercialization of the Red Raven Magic Mirror system, which quickly became a popular children’s entertainment product.

The song title and arranger/director has been removed for this example image

The Red Raven Magic Movie Records, introduced in 1956, embodied Morgan’s patented concept, offering children a unique blend of visual animation and music. The device consisted of a sixteen-sided mirror placed on the spindle of a phonograph, rotating in sync with a specially designed 78 rpm record that featured animated frames on its large label. As the record played, children could gaze into the Magic Mirror to see a charming animated scene that illustrated the accompanying song.

The Magic Mirror itself, as shown in the image, was a whimsical, carousel-like device that sat atop the record player’s spindle. As the record turned, the 16-sided Magic Mirror rotated in perfect harmony with it. The reflective sides of the mirror captured and “froze” the images on the record, holding each frame in place just long enough to create the illusion of continuous motion.

The Red Raven Movie Records were designed with children in mind, offering an enchanting experience that combined visual animation with music in a way that was both simple and magical. Advertisements from the time emphasized how easily these “living” records could bring thrilling animations to life right before a child’s eyes. The process was straightforward: parents or children would place a special Red Raven record on any 78 rpm record player, set the Magic Mirror over the spindle, and watch as colorful, animated scenes unfolded in sync with the music.

The operation of the Red Raven Movie Records was a clever and enchanting use of optical illusion and precise synchronization to create the appearance of animation. Each Red Raven record featured 16 distinct images, or frames, arranged around its large central label. These images were carefully interwoven into the design of the record so that when it spun at 78 RPM, they would be aligned with the 16 reflective sides of the Magic Mirror.

This precise synchronization of the spinning record and the rotating mirror produced a seamless animated sequence that brought the still images to life. As the music played, children would gaze into the Magic Mirror and see a lively, animated scene that perfectly matched the rhythm and story of the song. The result was a captivating blend of sound and motion that transformed the simple act of listening to music into an engaging visual experience.

These animations were more than just moving images; they were vibrant, detailed, and directly connected to the narrative of the songs. For instance, children could watch as a duck swam by, a frog leaped from lily pad to lily pad, or a parade of wooden soldiers marched and saluted—all perfectly timed to the music. This combination of sight and sound created an immersive experience that captivated young audiences and kept them entertained.

Moreover, the Magic Mirror itself was marketed as a durable and safe toy. Made from a combination of metal and plastic, it was described as “almost indestructible,” ensuring that it could withstand the rough handling typical of children’s play. This focus on safety and durability, coupled with the captivating animations, made the Red Raven Magic Movie Records a popular choice for families, offering a unique form of entertainment that brought stories and music to life in a way that was both innovative and fun.

The packaging of the Red Raven Movie Records was designed to immediately capture the attention of both children and parents. The box prominently displays the Magic Mirror and the colorful records, highlighting the vibrant animations that were a key feature of the product. The label, “Animated Cartoons Set to Music,” clearly communicates the product’s unique selling point: phonograph records that not only play music but also project full-color movies.

The packaging also emphasizes the toy’s suitability for young children, with a recommended ages clearly marked. The cheerful, circus-like design of the Magic Mirror itself, along with the bright colors of the records, adds to the overall appeal, making it clear that this is a fun and engaging toy.

Additionally, the image of children happily playing with the Magic Mirror on the box reinforces the product’s appeal as a safe and entertaining way to combine music and animation. The visual emphasis on the product’s interactive nature—children actively engaging with the phonograph and watching the animated scenes—further underlines its role as a source of joy and wonder for young audiences.

This eye-catching packaging played a crucial role in the product’s success, drawing in children and parents alike with the promise of a magical, musical experience that was both innovative and fun. The Red Raven Movie Records, with their unique blend of sound and animation, offered an enchanting form of entertainment that stood out in the crowded market of mid-20th century children’s toys.

This appeal to children was a key factor in the success of the Red Raven Movie Records, helping to sell approximately 500,000 sets and cementing their place as a beloved part of many mid-20th century childhoods.

As part of the Red Raven Movie Record series, a delightful collection of songs will be featured, including classics such as Little Bo-Peep, Three Little Kittens, Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, Three Blind Mice, Mary Had a Little Lamb, Old MacDonald Had a Farm, Raggedy Ann, Raggedy Andy, Parade of the Wooden Soldiers, Suzy Snowflake, Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town, Frosty the Snowman, Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, On the Merry-Go-Round (Umbrella Man), and Little White Duck. Most of these songs are credited to the Red Raven Orchestra under the direction of George S. Chase, a talented conductor and arranger who played a crucial role in crafting the orchestrated versions of these well-known nursery rhymes and holiday songs. Chase’s work, characterized by its rich orchestration and engaging melodies, perfectly complemented the visual animations that brought these stories to life for children. Although not much is known about Chase himself, his significant contributions to the Red Raven series made him a key figure in the creation of these beloved children’s records.

In addition to Chase’s work, other talented musicians contributed to the magic of the Red Raven records. For example, On the Merry-Go-Round (Umbrella Man) was adapted from the popular tune “The Umbrella Man,” originally crafted by the songwriting trio of James Cavanaugh, Larry Stock, and Vincent Rose. Cavanaugh was a prolific songwriter and lyricist from the Tin Pan Alley era, while Stock co-wrote several enduring hits like “Blueberry Hill” and “You’re Nobody ‘Til Somebody Loves You.” Rose, a composer and bandleader, is best remembered for his 1920 hit “Whispering.” Their contribution brought a piece of classic American music into the Red Raven series, ensuring its appeal to both children and parents alike.

on Columbia Records

Another notable figure in the Red Raven Movie Record series is Maury Laws, who collaborated on the song Little White Duck, performed by Betty Wells. Laws was an accomplished composer and musical director, particularly known for his work with Rankin/Bass Productions, where he scored iconic holiday television specials such as Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer and Frosty the Snowman. His involvement in the Red Raven series added a sophisticated musical touch, combining his expertise in orchestration with his deep understanding of children’s entertainment.

Together, these musicians and songwriters brought the Red Raven Movie Records to life, ensuring that the music was as enchanting as the animations themselves. Their work made these records a cherished part of many childhoods, blending sound and vision into a captivating and unforgettable experience.

Although the Red Raven Movie Records were marketed as durable, it’s clear that these cherished items have seen significant use over the years. Many of the records show signs of having been well-loved, though perhaps not always handled with the same level of care typically given to vinyl. Some records are cracked, their labels stained or even peeling off entirely, and they bear the usual marks of scratches from countless play sessions. The Magic Mirror viewer itself shows the effects of time and use, with tarnished mirror surfaces, dents, rust, a missing topper, and even something rattling inside.

Despite these signs of wear, every effort has been made to preserve the recordings and restore them digitally. The audio underwent a meticulous process of removing pops, clicks, and noise, while also enhancing sound quality to bring the music closer to its original form. The records were carefully scanned, and their labels were digitally edited to minimize imperfections before being converted into separate video files. However, one exception to this restoration process is the recording of Parade of the Wooden Soldiers. The record is missing the first few seconds of audio due to melting, and no audio enhancements were applied to this track. The decision was made to leave it as is, providing a comparison that highlights the extent of the clean-up efforts on the other recordings. If a better-preserved copy of the record can be found in the future, a new version will be uploaded to replace it.

Heavy damage including crack and melted spot covering first few rotations.

As we swim back to the present, it’s clear that the Red Raven Movie Records hold a special place in the hearts of many who grew up with them. These charming records not only brought the magic of animation into the home but also connected generations to the early innovations of pioneers like Reynaud. Although time may have left its mark on these treasures, the care and effort to preserve their magic remind us of the importance of cherishing and celebrating the unique ways sound and vision have come together to create joy. Until our next adventure, keep riding the waves of sound, and remember—every record has a story to tell!

Sources:

Websites:

- Birmingham Museums Trust. Praxinoscope, Birmingham Museums Trust, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=39737049. Accessed 31 Aug. 2024.

- Laws, Maury. Maury Laws: Composer, Arranger, Conductor. www.maury-laws.com/. Accessed 31 Aug. 2024.

- “Kevin Kiner.” IMDb, www.imdb.com/name/nm0493127/. Accessed 31 Aug. 2024.

- “The Talking Toy Hall of Fame™.” Phonographia, phonographia.com/TTHFFrameset-11.htm. Accessed 31 Aug. 2024.

- “Red Raven Magic Mirror Records Santa Disc – 1956.” Phonographia, phonographia.com/TTHF_MF_RR_Santa.htm. Accessed 31 Aug. 2024.

- “Red Raven Movie Records.” The Wolverine Antique Music Society Record Page, www.shellac.org/wams/wraven1.html. Accessed 31 Aug. 2024.

- “Red Raven Movie Records.” Discogs, www.discogs.com/label/904620-Red-Raven-Movie-Records?page=1. Accessed 31 Aug. 2024.

- “Rankin/Bass Composer and Arranger Maury Laws Dies at 95.” Variety, 28 Mar. 2019, variety.com/2019/music/news/maury-lewis-rankin-bass-composer-arranger-rudolph-dies-1203177202/. Accessed 31 Aug. 2024.

- Praxinoscope. Zoetrope, www.zoetrope.org/praxinoscope. Accessed 31 Aug. 2024.

Legal Cases:

- Morgan Development Laboratories, Inc. v. Watson, 188 F. Supp. 89 (D.D.C. 1960). Casetext, casetext.com/case/morgan-development-laboratories-inc-v-watson. Accessed 31 Aug. 2024.

Books:

- Tau, Michael. Extreme Music: Silence to Noise and Everything In Between. Feral House, United States, p. 58.

Magazines:

- Film Score Monthly, vol. 2, no. 65-76, 1996, p. 85.