Hello, fellow audio adventurers! I’m Finnley the Dolphin, your guide on a deep dive into the fascinating world of audio preservation. Today, we’re setting our sights on a remarkable tale that blends the industrial might of America’s oil history with the enduring legacy of sound recording. Get ready to explore the story of Amoco, a brand that not only fueled the engines of progress but also left a significant mark on the world of advertising and audio culture. From its early days as part of the Standard Oil empire to its innovative contributions in lead-free gasoline and memorable jingles, Amoco’s journey is one filled with pivotal moments and lasting impacts. So, let’s dive in and discover how this iconic brand shaped not just the fuel industry but also the soundscapes of American history.

The story of Amoco begins in 1889, when the Standard Oil Company established the Standard Oil Company of Indiana, centered around a refinery in Whiting, Indiana. This move was part of John D. Rockefeller’s ambitious strategy to dominate the burgeoning oil industry in the United States. As automobiles became increasingly popular in the early 20th century, Standard Oil of Indiana pivoted its focus to gasoline production, positioning itself as a key player in fueling America’s new mode of transportation.

The company’s early success was largely tied to its association with the Standard Oil Trust, but this relationship came to an end in 1911 when the U.S. Supreme Court ordered the dissolution of the Standard Oil monopoly. Emerging from the breakup as an independent entity, Standard Oil of Indiana began expanding its operations across the Midwest, supplying 88% of the region’s gasoline and kerosene by 1912. The company opened its first service station in Minneapolis that same year, marking the beginning of its direct engagement with consumers.

The 1920s and 1930s were periods of significant growth and innovation for Standard Oil of Indiana. In 1925, the company absorbed the American Oil Company, founded in Baltimore in 1910 by Louis Blaustein and his son Jacob. This acquisition allowed the corporation to operate under both the Standard and American (later Amoco) names, with the iconic red, white, and blue oval logo featuring a torch at its center. This branding became synonymous with reliability and progress, helping the company become the largest oil producer in the United States by the mid-20th century.

Amoco, as the company officially rebranded itself in 1985, was known for several key innovations. Among them was the introduction of lead-free gasoline decades before environmental concerns prompted broader changes in the industry. This move demonstrated Amoco’s commitment to technological advancement and environmental stewardship, setting it apart from many of its competitors.

The company’s growth continued through the post-war boom, expanding its reach both domestically and internationally. By 1971, all of Indiana Standard’s divisions bore the Amoco name, and the brand had become a household name across the United States and beyond. However, the most significant change came in 1998 when Amoco merged with British Petroleum (BP) in what was then the largest industrial merger in history. The new entity, BP Amoco, would later simplify its name to BP in 2001.

Following the merger, BP gradually phased out the Amoco brand, converting most of its service stations to the BP brand. The familiar torch and oval logo, which had once been a beacon of American industrial prowess, began to fade from the landscape. However, the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010 severely damaged BP’s reputation in the United States, leading the company to reconsider its branding strategy.

In 2017, BP announced the revival of the Amoco brand, reintroducing it to select markets across the eastern and midwestern United States. The decision to bring back Amoco was part of a broader effort to diversify BP’s brand presence in the U.S. and to distance itself from the tarnished BP name. By 2023, over 600 new Amoco stations had opened, marking a significant comeback for the historic brand.

Today, BP is once again converting some of its BP-branded stations back to Amoco, a nod to the brand’s enduring legacy and consumer trust. This strategy allows BP to maintain a strong presence in the U.S. market while leveraging the nostalgic and trusted Amoco name. The torch and oval, once a symbol of American innovation and reliability, continues to light the way for a new generation of consumers, blending history with the demands of the modern fuel industry.

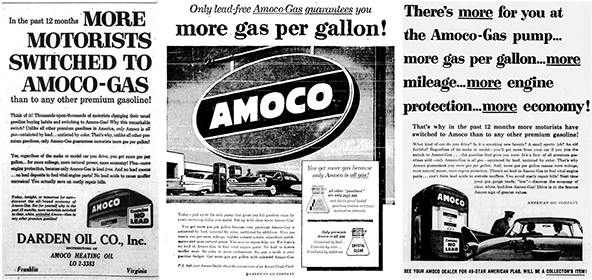

In the 1950s, AMOCO introduced a groundbreaking advertising campaign to promote their lead-free gasoline, which was a significant innovation at the time. Unlike the majority of gasoline on the market, which relied on tetraethyl lead and other additives to prevent engine knocking, AMOCO’s new fuel utilized advanced, proprietary compounds that achieved the same effect without the harmful environmental and health impacts associated with lead. This move was revolutionary, as leaded gasoline had been the industry standard for decades. AMOCO’s lead-free gasoline not only offered cleaner combustion but also positioned the company as a leader in environmental responsibility, long before such concerns became mainstream. Understanding that consumers might be skeptical of the performance and benefits of this new fuel, AMOCO invested heavily in a marketing campaign that spanned both print and radio, emphasizing the superior quality and safety of their lead-free product. The campaign, developed by The Joseph Katz Company, featured catchy jingles and powerful messaging, making it a memorable and influential part of advertising history.

Joseph Katz, a key figure in the advertising industry, was known for his ability to seamlessly blend business strategy with political savvy. His career, which spanned both commercial and political spheres, began to take off in 1922 when he partnered with The Strouse-Baer Co. of Baltimore, Maryland, to create an innovative advertising campaign for their nationally advertised line of Jack Tar Togs. This campaign, unveiled at the National Association of Retail Clothiers convention at Madison Square Garden, was designed to engage retailers more actively in promoting Jack Tar Togs, showcasing Katz’s forward-thinking approach to marketing. As the Director of Jack Tar Advertising, Katz played a pivotal role in enhancing the brand’s visibility and appeal, marking a significant achievement in his early career.

Katz’s influence extended beyond the commercial sector into the political arena. By the mid-20th century, his firm, The Joseph Katz Company, had established strong ties with the Democratic Party, particularly through its offices in Baltimore and New York. The Baltimore office was instrumental in producing political advertisements for Democratic senatorial campaigns in Maryland, while the New York office supported public relations efforts for the Democratic Party in New York. During a critical presidential election, Katz’s agency worked closely with the Democratic National Committee (DNC), managing key tasks such as purchasing radio and television time and overseeing other media-related aspects of the campaign.

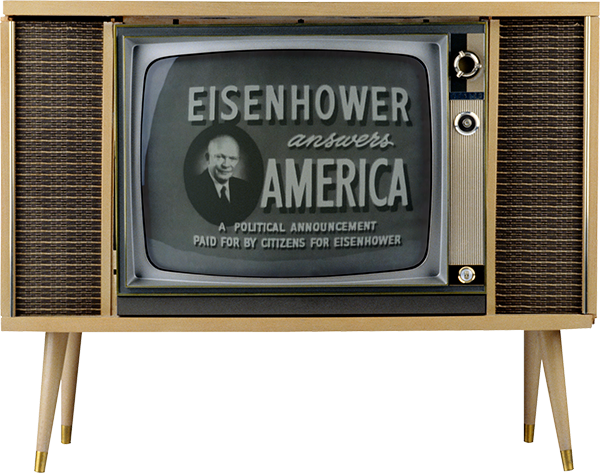

This period coincided with significant technological advancements that were transforming political campaigning. As mass media, including radio and television, became increasingly important, the expertise of advertising specialists like Katz grew in prominence. While some candidates, like Dwight D. Eisenhower, recognized the value of media consultants as strategic advisers, others, such as Adlai Stevenson, viewed them more as technical support. Nonetheless, the 1950s marked a turning point where political advertising became a vital component of campaigning, further cementing Katz’s legacy as a leading figure in both commercial advertising and political strategy.

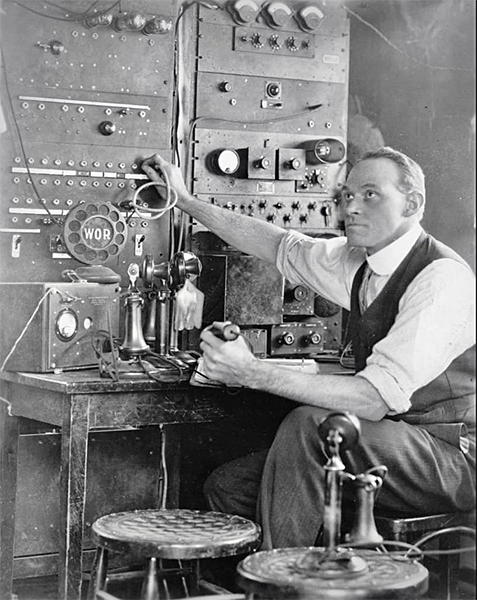

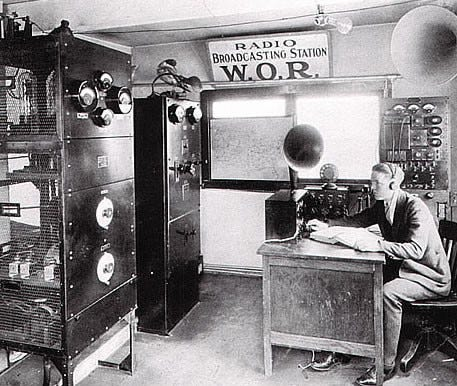

The AMOCO jingles were produced at WOR studios. WOR radio station, launched by Bamberger’s Department Store in Newark, New Jersey, in 1922, quickly became a pioneering force in radio broadcasting. The station’s early broadcasts, transmitted from a rooftop antenna and using a homemade microphone, helped promote radio receiver sales and established WOR as a significant player on the airwaves. WOR moved to its iconic 710 kHz frequency in 1927 and expanded its influence by opening studios in Manhattan, where it later became a founding member of the Mutual Broadcasting System.

Beyond its broadcasting prowess, WOR also developed a robust recording industry presence with its own recording studios at 1440 Broadway in New York City, operating from 1926 to 2005. These studios were associated with several record labels, including WOR Feature, WOR Recording, and Records of Knowledge. Under these labels, a variety of recordings were produced, including notable titles such as “The Popsicle Song” by an unknown artist, “A Doll House Christmas Eve” by Helen Kane, and significant historical recordings like “A Few Quotations From His Speeches” by Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “Voice Of Franklin Delano Roosevelt – A Few Quotations From His Speeches.” The studios also released albums like “Words That Shook the World,” featuring speeches by Winston Churchill and President Roosevelt. Today, WOR continues its legacy as a major radio station under the ownership of iHeartMedia, still broadcasting on 710 kHz from New York City.

The record produced with the AMOCO jingles would be sent to radio stations and to make it easier for the station DJs to queue the advertisements the record includes manual sequencing. Manual sequencing records date back to the early days of vinyl, when technological limitations and practical considerations shaped the way audio content was delivered. Unlike modern records, which are designed to play continuously from start to finish, manual sequencing records were intentionally crafted with separate tracks that needed to be accessed individually. This format was especially useful for educational materials, where a teacher or student could easily repeat specific sections of a lesson without having to navigate through an entire side of a record.

Manual sequencing records were particularly valuable for radio stations in the late 1950s, offering a crucial level of control for live broadcasting. They allowed DJs to select and play specific ads or content without accidentally advancing to the next track, ensuring precise timing during structured programming. These records also enabled stations to tailor content to different audiences by choosing the most relevant ads or segments, supporting the live and local nature of radio while maintaining high-quality broadcasts. However, while these records are excellent for radio, they present challenges when recording a video. The manual sequencing format requires clever editing to stitch together each track seamlessly, as each segment is designed to be paused and selected individually, making the process of creating a continuous video more complex.

As we resurface from our dive into the history of Amoco, it’s clear that this brand was more than just a provider of gasoline—it was a pioneer in both environmental responsibility and the art of communication. From revolutionizing fuel with lead-free options to crafting memorable advertising campaigns, Amoco’s legacy is one of innovation and influence. The story of its rise, merger with BP, and eventual revival is a testament to the enduring power of a brand that once lit the way for American industry and continues to shine in the world of audio preservation. So, whether you’re an audiophile, a history buff, or simply someone who loves a good story, I hope you’ve enjoyed this journey into the world of Amoco. Until next time, keep your ears tuned and your spirit adventurous—there’s always more to explore in the ocean of sound!

Sources:

“More Gas Per Gallon.” The Morning Union, 23 June 1959, p. 29. Newspapers.com, https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-morning-union/150372036/. Accessed 18 Aug. 2024.

“Ad for DARDEN OIL CO., Inc.” Tidewater News, vol. 54, no. 56, 16 July 1959. Virginia Chronicle, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=TDWNS19590716.1.2&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN——–. Accessed 18 Aug. 2024.

“More Gas Per Gallon.” Plattsburgh Press-Republican, 12 May 1958. NY State Historic Newspapers, https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=pp19580512-01.1.12&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN———-. Accessed 18 Aug. 2024.

MShipphoto. “The World’s Largest AMOCO Sign Perched on the Roof of a Down-to-Earth Gas Station, St. Louis, Missouri, USA, 20 Dec. 2019.” Shutterstock, www.shutterstock.com/image-photo/st-missouri-usa-12-20-2019-1627795279. Accessed 18 Aug. 2024.

Bush, Logan. “A Massive Amoco Gas Sign, the Largest of Its Kind, St. Louis, Missouri, 18 May 2015.” Shutterstock, www.shutterstock.com/image-photo/st-louis-missouri-may-18-2015-1642196503. Accessed 18 Aug. 2024.

LaMonica, Michael. “Vintage American Gasoline Gas Pump, Hague, New York, 17 July 2008.” Shutterstock, www.shutterstock.com/catalog/collections/3437440161191822370-e24124d54469145dec07a43745815a322965c2df8bcc253f7503c94f78030f9c. Accessed 18 Aug. 2024.

“Page 102.” The Clothier and Furnisher, vol. 101, 1922, p. 102. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, digitized 7 Mar. 2011. Accessed 18 Aug. 2024.

“New Stations.” Radio Service Bulletin, 1 Mar. 1922, pp. 2-3. HathiTrust Digital Library, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=osu.32435066705633&view=1up&seq=228&q1=WOR. Accessed 18 Aug. 2024.

Dunning, John. On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio. Revised ed., Oxford University Press, 1998, pp. 117–118.

Moriyama, Takahito. Empire of Direct Mail: How Conservative Marketing Persuaded Voters and Transformed the Grassroots. University Press of Kansas, 2023, p. 23.

“History of the Standard Oil Company Signs.” Garage Art, www.garageart.com/history-of-the-standard-oil-company-signs/. Accessed 18 Aug. 2024.

“Standard Oil Company (Indiana) History.” Auke Visser’s International Super Tankers, www.aukevisser.nl/others/id880.htm. Accessed 18 Aug. 2024.

“Some BP Gas Station Owners Switching Brands Because of Gulf Oil Spill.” NOLA.com, 7 July 2010, 2:44 PM, www.nola.com/news/gulf-oil-spill/index.ssf/2010/07/some_bp_gas_station_owners_swi.html. Accessed via Internet Archive, 18 Aug. 2024.

“WOR Feature.” Discogs, www.discogs.com/label/867695-WOR-Feature. Accessed 18 Aug. 2024.

“WOR Studios.” Discogs, www.discogs.com/label/282587-WOR-Studios?page=1. Accessed 18 Aug. 2024.

“WOR Recording.” Discogs, www.discogs.com/label/134840-WOR-Recording?page=1. Accessed 18 Aug. 2024.

“Records of Knowledge.” Discogs, www.discogs.com/label/440128-Records-Of-Knowledge?page=1. Accessed 18 Aug. 2024.

“WOR Radio Engineer Seth Gamblin Sits at Control Board, New York, New York, Mid-1920s.” Pinterest, https://es.pinterest.com/pin/wor-radio-engineer-seth-gamblin-sits-at-control-board-new-york-new-york-mid-1920s-in-2023–626985579393297727/. Accessed 18 Aug. 2024.

Hinckley, David. “WOR Turns 100: Maybe This Radio Thing Worked Out After All.” Medium, 4 Dec. 2022, https://dhinckley.medium.com/wor-turns-100-maybe-this-radio-thing-worked-out-after-all-dec2f094cd4. Accessed 18 Aug. 2024. Photo used: “WOR in the Olden Days.”